In the early 1970s, the ‘angry young man’ manifested itself as a central character in Indian films. Mostly played by star persona Amitabh Bachchan (1942-), the angry young man expressed themes of anti-establishment and socio-political disturbance.[1] In his characteristic role as a criminal anti-hero (Deewaar, 1975, Muqaddar Ka Sikandar, 1978), Bachchan often became the victim of either his own passionate love for a woman or the socio-financial hardships of family life in Bombay.

The angry young man series can be interpreted as an example of what Jigna Desai and Rajinder Dudrah define ‘Masala cinema’. Masala films draw on multiple aspects of Indian popular culture for their appealing filmic mixtures of romance, comedy, city underworld crime, melodrama and sometimes even martial arts.[2] More important though is that Masala cinema ‘may be seen to represent the hopes and anxieties of the everyman and woman in a fast changing world’.[3]

In this essay, I argue that this idea of self-identification (that means, the film text as a mirror for the socio-political hopes and anxieties of the common civilian) directly links the angry young man series to a more contemporary example of Masala cinema. My thesis is that the (criminal?) anti-hero of Neeraj Pandeys A Wednesday (2008), labeled the ‘common stupid man’ at the end of the film, can be seen as a modern personification of Bachchans angry young man. Furthermore, I hope to demonstrate how this ‘common stupid man’ radically expresses the fears and anxieties that torment Indian society in a post 9-11 context.

The real mission

The anti-hero of A Wednesday initially presents himself as a typical terrorist. On a common Wednesday, he calls Bombay police officer Prakash Rathod to inform him that five bombs have been planted throughout the city. The police has to free four infamous militants in order to prevent detonation. Until so far, it is entirely clear that there can be no sympathy for the bomber. This changes when the actual identity of the bomber is revealed. The character of Naseeruddin Shah is no terrorist, but a common civilian, who lied about the nature of his mission. In fact, he didn’t want to free the militants, he wanted to kill them. His goal was to avenge several terrorist attacks that were executed in Bombay and other Indian cities. Shah explicitly refers to several bombings, including one that occured only two years before the film was made (July 11th, 2006).[4] One of the most significant pieces of dialogue explicates the leading motive for Shah’s deeds:

‘’ I am someone who is afraid to get in a train or bus these days. (…) I am (…) the one who is afraid to grow a beard and wear a cap. I am the first one to get killed. You must have seen a crowd. Choose a person from it. I am that person.’’[5]

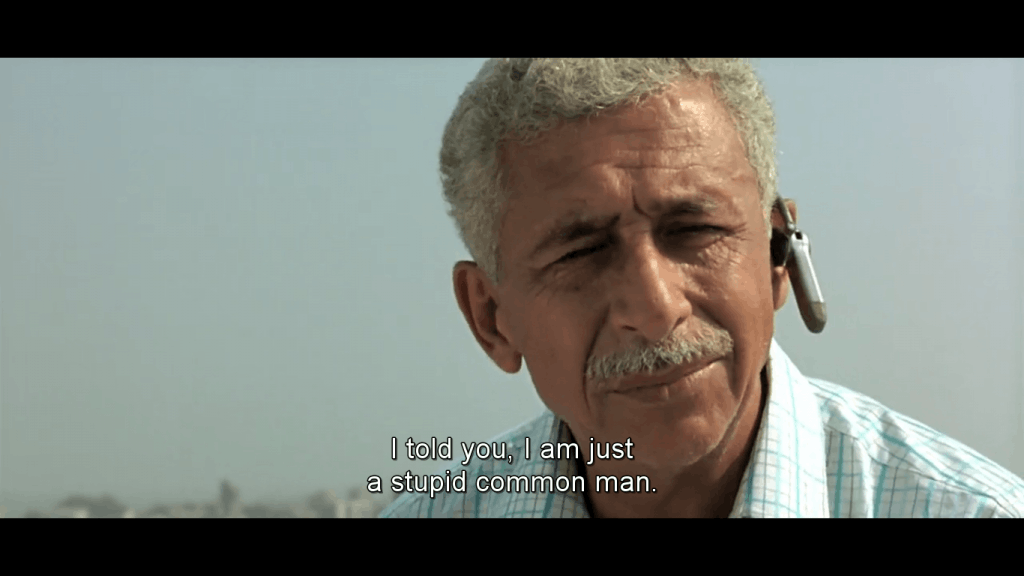

Throughout his monologue, Shah frames himself as the ‘common stupid man’, saying he is ‘’just the ‘common stupid man wanting to clean his house’’. The term is repeated a few times, implying that it is an important characterization (notice also that the actual name of Shah’s character is never revealed).[6]

Shah’s explanation points out that fear for terrorism, or fear for his own safety, drove him into this action of revenge. Shah critizices the government for its passivity in punishing the terrorists who were behind the bombings.[7] As the Bombay train bombings actually took place (among other terrorist attacks), you may state that other civilians could hypothetically relate to the fear of the common stupid man. The character of Naseeruddin Shah could thus be seen as a metonymia for the fears of Indian society.

The absence of political judgement

What is important here is the refusal of the film (I prefer this term above ‘the director’ or ‘the screenwriter’, in order to prevent unjust framing) to ultimately judge the civilian for his actions. While the five bombs from the film’s opening weren’t really planted, three of the four militants died in an explosion on a military airport, after which Shah succesfully commanded the present police officers to kill the fourth. The two police officers consciously legitimize their own killing of a convicted militant when one of them shoots his colleague in the arm, implying that the terrorists tried to escape.

At the end of the movie, Prakash Rathod and the common stupid man meet when they (respectively) leave from and arrive at the building that served as an instruction post for the bomber. Rathod obviously knows that it is the bomber who is passing by, but he chooses to let him go:

‘’I never ever imagined that a common man could go to such stage. (But) One common man had the guts. This incident is not registered in any file. (…) But it is in my mind.’’

The rhetorics of the common stupid man

Retrospectively, the main character of A Wednesday is not Prakash Rathod. It’s the common stupid man, who dares to challenge the authorities out of fear for his own safety.

In the angry young man series, socio-financial hardships or histories of injustice in family life legitimized the coming into existence of the criminal (and angry) young man; the leading underworld figure in Deewaar , the snitch who is selling out smugglers and other criminals in Muqaddar Ka Sikandar. The fictional circumstances that Bachchan had to deal with often mirrored reality.[8] The narrative of A Wednesday implies a similar connection between fiction and reality. The most poignant fear of Indian society is channeled through the dialogues and deeds of a single character, namely the common stupid man. Naseeruddin Shah is playing the anti-hero that Amitabh Bachchan typically portrayed in the 1970s, only the context is different and the term is slightly transformed. Both characters committed crimes they could be punished for, but they are not: they serve to represent the dreams and anxieties of Indian men and women in a world that is ever changing.

Literature

Dudrah,

Rajinder and Jigna Desai. The Bollywood

Reader. Berkshire: Open University Press, 2007.

Ganti, T. Bollywood: a Guidebook to

Popular Hindi Cinema. London: Routledge, 2004.

Websites

Ghosh,

Amitav. ‘’India’s 9/11? Not Exactly’’. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/03/opinion/03ghosh.html

(Accessed May 17th, 2018).

Lal, Vinay. ‘’How Vijay Was Born: Bachchan’s Urban Landscapes’’. https://vinaylal.wordpress.com/tag/the-angry-young-man-in-hindi-cinema/

(Accessed May 17th, 2018).

Sen, Sudhi Ranjan. ‘’Terror Response after 9/11: What US did and India

didn’t’’. https://www.ndtv.com/world-news/terror-response-after-9-11-what-us-did-and-india-didnt-467320

(Accessed May 16th, 2018).

Film

Pandey,

Neeraj. A Wednesday. UTV Home

Entertainment, 2008.

[1] Vinay Lal, ‘’How Vijay Was Born: Bachchan’s Urban Landscapes’’. https://vinaylal.wordpress.com/tag/the-angry-young-man-in-hindi-cinema/ (Accessed May 17th, 2018). T.Ganti, Bollywood: a Guidebook to Popular Hindi Cinema (London: Routledge, 2004), 30-33.

[2] Rajinder Dudrah and Jigna Desai, The Bollywood Reader (Berkshire: Open University Press, 2007), 12.

[3] Dudrah and Desai, The Bollywood Reader, 11.

[4] The four terrorists refer to actual bombings in Mumbai, Delhi, Gujarat and Malegoan (1992, 1993, 2006).

[5] This piece of dialogue actually belongs to a ten minute-monologue that helps to understand the motive of the bomber and the ideas about the common (stupid) man that I will elaborate upon in this essay. 1.21.10-1.31.10.

[6] At the beginning of the film, a news reporter is interviewing a common man (who also frames himself: ‘a common man like me’) who fell into a pothole that was either dug or initiated by (representatives of) the government. The common man firmly criticizes the government and holds it responsible for what happened (‘are their potholes in the city or is the city in potholes?’), but what is especially interesting: he only does this after the news reporter and her cameraman have insinuated (in a scene taking place about five minutes earlier in the film) that they should give him some lines for the tv fragment. The first time they asked him some questions, the ‘common man’ had actually nothing to say. The little ‘conspiracy’ of the news reporter and her cameran implies that they explicitly want this man to be critical on the government.

[7] A piece of dialogue from the film: ‘’ All of you. The government, police force, intelligence, is capable of carrying out this pest control. But you are not doing it. Instead you are supporting their cause by not doing anything stringent…. Don’t you think this is a question mark on your ability?’’ This critique actually mirrors the content of opinion pieces that can be found on the world wide web, for instance: Sudhi Ranjan Sen, ‘’Terror Response after 9/11: What US did and India didn’t’’, https://www.ndtv.com/world-news/terror-response-after-9-11-what-us-did-and-india-didnt-467320 (Accessed May 16th, 2018). But there are significant counter-opinions too: Amitav Ghosh, ‘’India’s 9/11? Not Exactly, https://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/03/opinion/03ghosh.html (Accessed May 17th, 2018).

[8] Vinay Lal, ‘’How Vijay Was Born: Bachchan’s Urban Landscapes’’. https://vinaylal.wordpress.com/tag/the-angry-young-man-in-hindi-cinema/ (Accessed May 17th, 2018).

I wrote this essay for a course on modern contemporary film movements, University of Antwerp, spring 2018.