In the course of March and April 2019, I wrote seven essays on topics ranging from a supposedly blasphemous song to the relationship between subjectivity and anthropological fieldwork. Today I publish the first essay, on Robin Hardy’s 1973 cult classic The Wicker Man.

In pastures green he leadeth me

The reconfiguration of space and authority in The Wicker Man

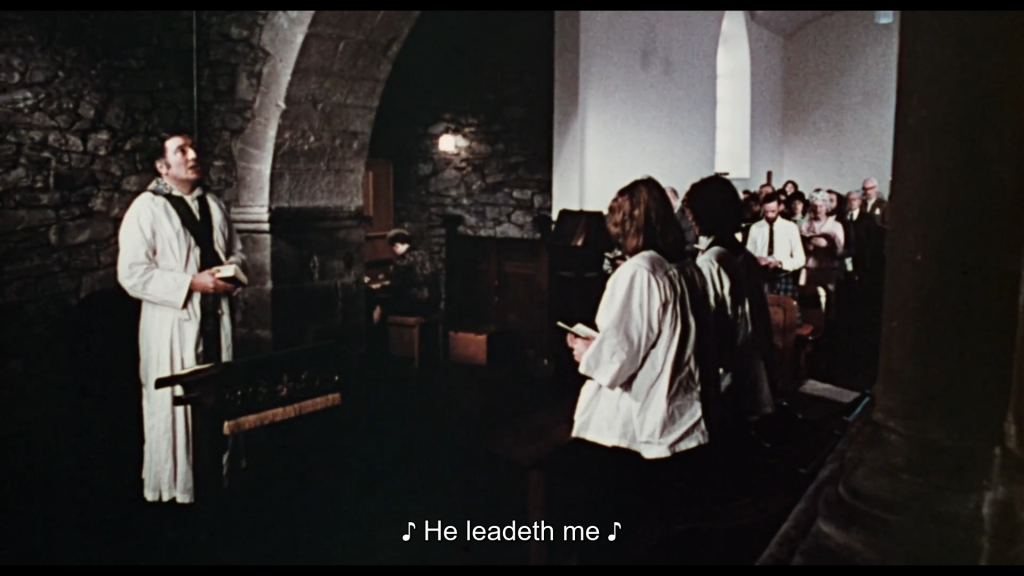

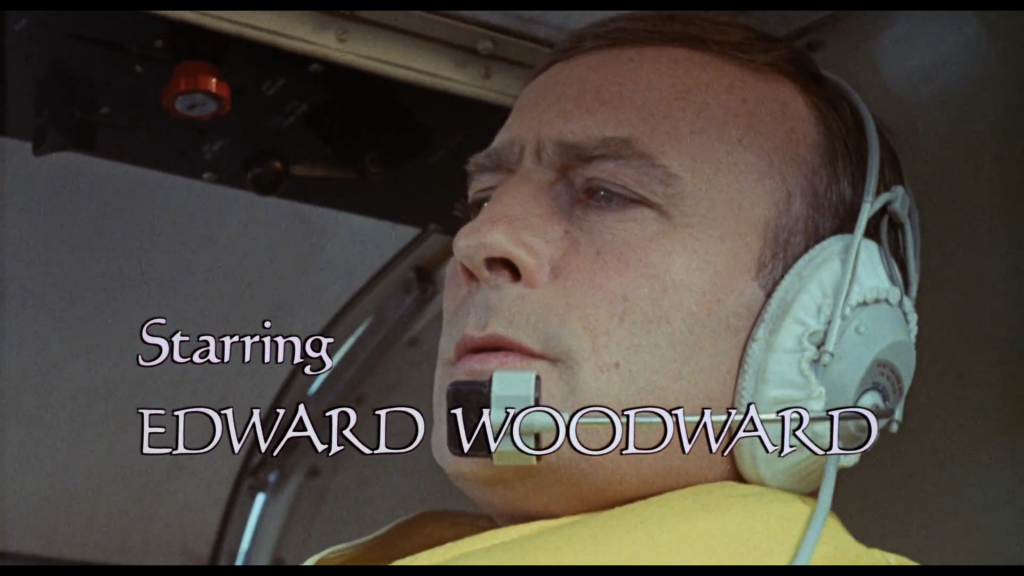

Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man (1973) opens with a church service. ‘’The Lord’s my Shepherd’’, the white-plastered walls echo, ‘’in pastures of green he leadeth me’’ (Psalms 23). The first shot appears as a close-up of two hands holding a book with a black cover; one could see a songbook for the liturgy and yet think of a Bible. As the camera is swiftly zooming out, we see the full posture of a middle-aged man (played by Edward Woodward), who is singing his heart out before he delivers a sermon on the Last Supper. The continuing sermon monologue is intercut with two shots in which sergeant Howie [the credited character] actually receives a piece of bread and a cup of wine.

In these two minutes of orientation and establishment, the politics of the space are similarly politics of comfort and authority, especially once we reconstruct the scene as a comfort zone for the protagonist. Nearly intangibly, Howie transforms from a regular member of the church community (illustration 1) into a preacher, someone who claims authority by means of a clear disposition. Notice how an impressive bended mosaic is looming in the background while Howie is delivering the sermon (illustration 2); the space looks illuminated and severe, whereas the actual or formal pastor is standing in a dark alcove (illustration 3). The first sentence of Howie’s sermon, then, reads as a proclamation: ‘’I have received of the Lord that which I also delivered unto you’’. Howie is not the appointed preacher in this service, but he certainly acts like one.

Above: illustration 2. Below: illustration 3.

The Wicker Man demonstrates how religious authority can be dismantled and deconstructed once we enter another space. In this regard, space once again refers to the politics of a concrete geographical space informing and constructing politics of comfort and authority. After the film’s opening service, we witness the majestic flight of a hydroplane, transporting a familiar passenger from his initial comfort zone to a space of discomfort and anti-structure (anti-structure in Turner’s sense of liberation and liminality[1] on behalf of the people will encounter after the flight – as I will demonstrate, this is a deeply uncomfortable environment for Howie) (illustration 4 and 5).

Illustration 4 & 5

I write down these terms (‘discomfort’, ‘anti-structure’) with hindsight. I have seen the film multiple times – I know that a future scene will feature the antagonist of the film (or is it the protagonist?) declaring to Howie that he is a fool, indicating that Howie’s self-proclaimed authority has been subject to the elements of disruption and play: ‘’for you have accepted the role of king for a day, and who but a fool would do that’’? The antagonist (or the protagonist?) speaking here is the Lord of Summerisle (played by Christopher Lee), Summerisle being the island at which Howie arrives at the end of the hydroplane sequence.

On this island people unanimously worship the Celtic gods of their presumed ancestors, hoping that a gift from the gods may bless their harvest. Summerisle’s teasing reference to the fool and the king displays the anti-structure (seen through Howie’s lens) that challenges Howie’s urge for a tangible protestant (power) structure.

When Howie steps out of his hydroplane, wearing his police costume, he asks the islanders to send a dinghy. They instantly refuse, arguing that Howie needs a written permission from ‘his Lordship’ to enter their private property. It does not matter that he is a police man probing the disappearance of a young teenager. On Summerisle, authority is established and perpetuated by means of the islanders’ distinctive political and religious configuration of space. If we would invoke Weber’s tripod of authority modes, this is about the clash of rational authority and an entanglement of traditional (‘’the old gods are still alive here’’, says Summerisle) and charismatic (Summerisle’s leadership) authority.[2]

To say it rather bluntly, this is what The Wicker Man is all about: we see a man who is trying to reconcile his Victorian politics of comfort and authority with a space that defies and challenges everything he stands for. Being a police man on an island that disrupts his self-proclaimed authority as a Man of Law, Howie can only try to artificially restore the space of anti-structure as a space of structure:

Illustration 6

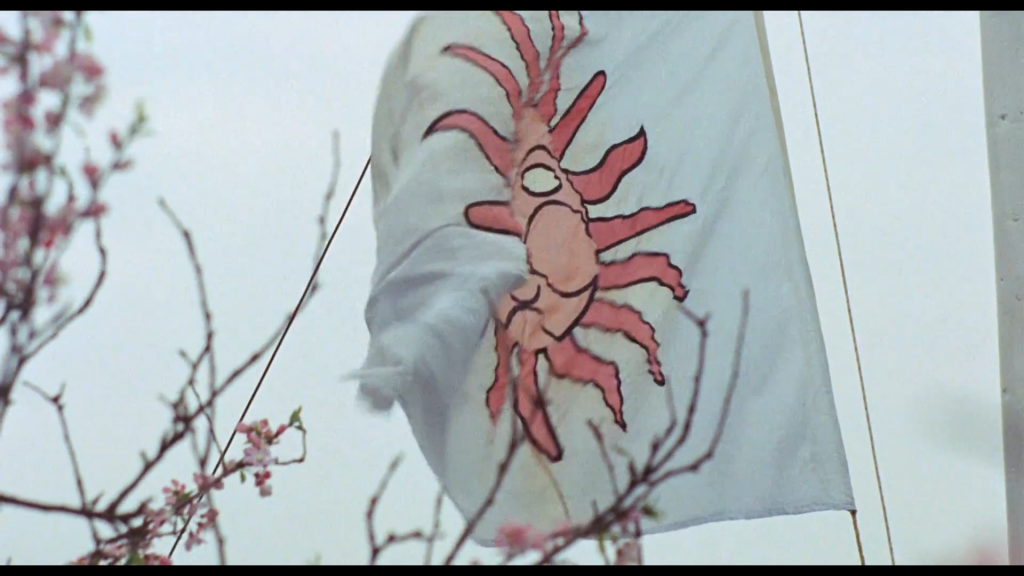

The Wicker Man consciously plays out Howies failure to do so. The closed space of Summerisle is a trap: it is the locus of a signifying waving flag (illustration 7) that echoes the solstice we see even before the opening scene in the church (illustration 8). In the credits we read that The Wicker Man is ‘a Summerisle release [production]’ (illustration 9). With ironical hindsight, again, we know that Howies fate is sealed once we see the waving Summerisle flag upon his arrival.

Illustration 7

Illustration 8

Illustration 9

Why, then, is this film discursively interesting and important in a Religious Studies context? I provide three perspectives that could possibly initiate papers that combine scholarly insights, mainly from the fields of material religion, semiotics and anthropology, with the rhetorics of The Wicker Man:

- The film implicitly engages in the academic discourse of ‘belief’ or ‘meaning’ [framed as a protestant bias or unjust former preoccupation in the study of religion] as contrasted to the relevance of practices, gestures and material objects.[3] The religious affiliations of the islanders are embodied and practiced. Their faith is intrinsically connected to a material configuration of space through ritual, music and daily practice. This configuration deeply disturbs Howie, who is deliberately trying to reconfigure his ‘inner convictions’ in exterior (i.e. material) ways (illustration 6). In fact, The Wicker Man could be examined in the light of Matthew Engelke’s thesis that ‘’all religion [i.e., also Howie’s religion] is material religion’’.[4]

- The people of Summerisle defy protestant semiotics. ‘’We do not use the word ‘dead’. The soul returns to the life forces in another form’’, one of the islanders claims. I find Webb Keanes notion of semiotic ideologies particularly apt to study The Wicker Man, precisely because the semiotic notions in this film are continuously inseparable from their material consequences.[5] The semiotic difference between ‘resurrection’ and ‘reincarnation’ inevitably shapes your interpretation of the ambiguous and horrifying final sequence.

- Robin Hardy (the director) and Anthony Shaffer (the screenwriter) based their film on passages from James Frazer’s The Golden Bough (1890), taking these as historical rather than folkloristic descriptions of Celtic rituals and practices.[6] While the film was intended to be a response to the new age and pagan countercultures of the 1960s and 70s, the film was actually praised by a lot of these people[7]. The Wicker Man ultimately became a cult and horror classic that got disconnected (at least, in terms of its popular reception) from the Frazer texts that inspired the film. I am sure that a intriguing essay could be written on the basis of this information, as we also discussed the film extensively in a Doing Research class (and screening) with Jo Spaans (4 April 2019).

Bibliography

Engelke, M. ‘’Material Religion’’. In R.Orsi (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Religious Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012. 209-229.

Franks, B. ‘’Constructing ‘’The Wicker Man’’’’’. Chap. 3 in J. Murray, L. Stevenson, S. Harper and B. Franks, eds., Constructing ‘’The Wicker Man’’: Film and Cultural Studies Perspectives. Glasgow: University of Glasgow, Crichton Publications, 2005. 63-78.

Koven, M.J. ‘’The Folklore Fallacy: A Folkloristic/Filmic Perspective on ‘The Wicker Man’’’’. Fabula 48 (2007): 270-280.

Meyer, B. and D. Houtman. ‘’Introduction – How Things Matter’’. In D. Houtman and B. Meyer, eds., Things: Religion and the Question of Materiality (New York: Fordham University Press, 2012), 1-23.

Turner, V. From Ritual to Theatre: the Human Seriousness of Play. New York: PAJ Publications, 1982.

Notes

[1] V. Turner, From Ritual to Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play (New York: PAJ Publications, 1982), 44.

[2] B. Franks, ‘’Constructing ‘’The Wicker Man’’’’, in J.Murray, L. Stevenson, S. Harper, B. Franks, eds., Constructing ‘’The Wicker Man’’: Film and Cultural Studies Perspectives (Glasgow: University of Glasgow, Crichton Publications, 2005), 65, 67.

[3] B. Meyer and D. Houtman, ‘’Introduction – How Things Matter’’, in D. Houtman and B. Meyer, eds., Things: Religion and the Question of Materiality (New York: Fordham University Press, 2012), 1-3.

[4] M. Engelke, ‘’Material Religion’’, in R. Orsi (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Religious Studies (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 209.

[5] Engelke, ‘’Material Religion’’, 218-221.

[6] M.J. Koven, ‘’The Folklore Fallacy: A Folkloristic/Filmic Perspective on ‘The Wicker Man’’’, Fabula 48 (2007), 270.

[7] Franks, ‘’Constructing ‘’The Wicker Man’’’’, 63, 73-74.

Een gedachte over “In Pastures Green He Leadeth Me: The Reconfiguration of Space and Authority in The Wicker Man (1973)”