The [English] paper that I submitted below is the result of my efforts for a master course on conversion. My intention has been to combine theoretical reflections on conversion [‘can you also convert to secularity?’] with a textual & formal analysis of a specific film (Kreuzweg, or Stations of the Cross, Dietrich Brüggemann, 2014). I argue that this film perpetuates a rigid binary between ’the religious’ and ’the secular’ and I question the ideological implications underneath.

Condemned to Death: Religious Sacrifice and the rejection of secular conversion in Kreuzweg

Tim Bouwhuis

In a 2014 article for Numen, S.N. Balagangadhara, a Belgian professor in comparative religious and cultural studies, assesses what he describes as the attempt of the contemporary liberal state to perpetuate a binary opposition between religion and the secular.[1] Balagangadhara concisely elaborates on the historical origins of a theological triad within early Western Christianity, in which ‘true religion’ and ‘false religion’ conjoined with a more or less neutral connotation of the secular. According to the author, inhabitants of the premedieval Roman Empire were free to engage in certain practices that did not relate to the dichotomy of true and false religion. Among these practices were weddings, ceremonies related to betrothals and name-giving ceremonies.[2]

Nowadays a ‘secular’ sphere is predominant in the configuration of our public space, our laws and our human rights. Obviously that does not mean that religious matters have been disentangled from secular Western societies completely. But the positions and various assessments of what is labelled ‘religious’ fundamentally diverge from similar discursive frameworks in supplanting theologies.[3]

In an exemplary secular state, authorities take an agnostic stance towards religion. They embrace leading theological worldviews within the boundaries of their societies, but these worldviews play no defining role in dominant policymaking. Instead, they are tolerated within the realm of the secular, because the state is ‘’pleading inability to determine the truth in matters of religion’’.[4] Thus, the idealized worldview of the secular state entails a binary: a binary between religious and secular matters.[5] The separation between the two is strict and definitive.[6]

The existence of this religious-secular binary has been heavily criticized in academic circles. Religious Studies scholar Timothy Fitzgerald has argued that ‘’none of these [two] categories has fixed meanings’’, while they are ‘’fundamentally rhetoric and strategic’’ at the same time.[7] In addition, Talal Asad (whom I will return to later in this paper) stated that the distinction between the religious and the secular has been detrimentally framed within the popular idea that the religious precedes the secular, marking a spectacular break between the two as soon as (an essentialized notion of) the secular enters the stage.[8]

Film, ideology and conversion

In this paper, I’m not so much interested in the academic discourse and relating truth claims regarding this contested discursive validity of the religious-secular binary. What I do find fascinating though is how echoes of this binary can emphasize their own existence – modified and twisted, but still recognizable – in cultural products.[9] Cultural products, and more particular, films that originate in secular contexts, can lineate with discursive ideologies in various ways. Regardless of questions of ‘truth’, binaries and juxtapositions can live their own lives in the contexts of audiences that are (hypothetically) shaped by secular values.[10]

The main objective of this paper is to probe the lingering presence of a religious/secular-binary in arthouse drama Kreuzweg (or Stations of the Cross; Germany, Dietrich Brüggemann, 2014). The film features a female protagonist that has been socially conditioned by religion: Maria, a young, fourteen year old-girl, who loses herself in her unconditional path towards Catholic confession. By analyzing the film’s style and script, I will investigate to which extent Kreuzweg fits a discursive paradigm of the religious in juxtaposition to the secular.

In addition, I hope to demonstrate how Kreuzweg is caught in its paradoxical stance towards conversion as change. This stance entails a rigid dichotomy between religious conversion and secular conversion, that is framed through the poignant gap that separates the protagonist’s ideal ideals/desires and her repressive and imprisoning reality. I use both Matthew Scherers [2011, 2013, 2015] and Talal Asads [1996, 2003] critical reflections on secular ‘conversion’ (a tandem of two seemingly contradicting words) to assess the ways in which Kreuzweg uses a religious/secular-binary to frame its protagonist’s individual convictions. In other words, I will focus on filmily embedded notions of conversion through the lens of the religious-secular binary. I will use the work of Asad and Scherer to argue how prevailing notions of secular conversions, or conversions to modernity, are often shaped by rhetoric and processes of change that resemble simplified views on religious conversion. The next step will then be to ask to which extent these paradoxical notions of secular conversions are made visible in Kreuzweg.

By researching the relation between the religious-secular binary and a contemporary conversion story in the selected fiction film , I hope to show in which ways the identity of Kreuzweg’s female protagonist, who has gotten entangled in a complex process of change through religious and/or ‘secular’ conversion, is shaped and reshaped through rather discursive notions on the implications that two intrinsically separated ‘states of being’ (in terms of identity), namely ‘being religious’ and ‘being secular’, have for the character development of the 14 year old Maria. Although the film makes no explicit use of the term ‘secular’, I will argue that its framings of conversion as change is based on a rigid understanding of the religious/secular-binary (i.e. what it means to be ‘religious’ ‘versus’ what it means to be ‘secular’). The discursive roles of conversion in the process of identity formation, discussed solely with regard to the selected film, will thus be embedded into the tense framework of the hypothetically present religious-secular binary.

I have to underline that the goal of this paper is not to offer or propose more nuanced views on either conversion or ‘the’ secular. Instead I’m interested in the notions of conversion that is suggested (mainly) by the film’s screenplay, and, more particularly, in the implicit views on secular conversion that tends to lurk behind the rather straightforward story of religious conversion.

On method

Within the scope of this paper, I won’t use a uniform method for film analysis. Instead, I will elaborate mainly on elements of film style (by means of selected screenshots) and film text (by means of the screenplay). Although it is tempting to connect some of the more rigid characterizations to the possible ideologies of the filmmaker or screenwriter[11], I will consciously ‘limit’ myself to the visual and textual elements that are encapsulated within the film itself. I place limit between brackets here, because I actually believe you reduce the potential of your argumentation when you pay too much attention to questions of authorship.[12] Spectators look at the film rather than the director’s statement; film analysis, then, may provide the best (and most probably the only) and most flexible method to presume, to some extent, in which ways the films could possibly be perceived by contemporary audiences without asking it to specific spectators. Unfortunately I cannot engage in the practice of assessing spectatorship within the scope of this paper; nevertheless, it will hopefully become clear how my argumentation could provide fascinating starting points for research into cultural values and possibly even performativity.

One practical note is that I use the English subtitles for the German language that is spoken in the film. If this, in any case, implies that the profundity of script information inevitably gets lost in translation, I take full responsibility for this pragmatic choice.

To conclude, I will try to answer the question that steers my film analysis: To which extent does Kreuzweg perpetuate a binary between the religious and the secular in terms of its attitude towards conversion as change?

I: Conversion: can you convert to the secular?

On first sight, Talal Asads and Matthew Scherers work on politics and secularism doesn’t seem to match with the diffuse phenomenon we call ‘conversion’. We might conceive of conversion as a practice or process that occurs in ‘religious’ contexts only. Talal Asad even claims that ‘there was a time that conversion didn’t explaining’.[13] In this rather simplistic line of thought, you may convert to a religion either because it just happens to you, or because you are curious what is involved in living a ‘religious’ life. Conversion then justifies itself. You don’t have to argue why you are or have been converted. It’s a fact of life, an unquestioned truth.[14]

The importance of this particular conception of conversion lies in the ways both Talal Asad himself and Matthew Scherer have adopted it to address and assess contemporary turns to the secular, presumably understood by Asad as a synonym for or extension of modernity. In the words of Asad, ‘’most individuals enter modernity rather as converts enter a new religion – as a consequence of forces beyond their control. ’’.[15] He then argues that the complete subtraction of ideas about power that this mindset implies rests on the illusion of ‘free choice’. Modernity, says Asad, defines the choices of individuals, fully in line with the ways in which a religion (Asad doesn’t specify religion here) defines the choices of a fresh convert.[16] This rigid argumentation seems to suggest that existence is always steered by ideology.

In Formations of the Secular (2003), Asads offers a more nuanced formulation on the position of the individual in what is now seems to be addressed as a derivative of secularity (instead of modernity). Secularists, he states, ‘’ are alarmed at the thought that religion should be allowed to invade the domain of our personal choices—although the process of speaking and listening freely implies precisely that our thoughts and actions should be opened up to change by our interlocutors”.[17] Within this conception of ‘secular’ identity, the pivotal paradox lies in the illusion of agency and free choice.

Matthew Scherer uses Asads idea as one of his starting points to analyze the politics of secularism in the contemporary West. His most important book, Beyond Church and State (2013), already bears in its title the argument that the normalized binary between ‘Church’ (to be interpreted as a metonymy for religion) and (the secular) State cannot serve to address the complexity of actual political contexts.[18] I now focus on one essential element of Scherers argument, namely the idea that the figure of conversion can be used to understand how secularism produces secular identity. For Scherer, conversion is most fundamentally ‘’a transformational process of ethical character formation and communal reorientation that is retrospectively consolidated through the production of a new narrative self-identity’’.[19] A conversion is not necessarily ‘’religious’’, unless it is framed in that way.[20] Scherer argues that proponents of the secular have failed to acknowledge that secularism has its roots in a religious past.[21] What they present is a rupture, a paradigm shift; a simplifying narrative of separation subsequently serves to circumnavigate the fact that the actual process towards secularism has been one of transformation, ethical character formation and communal reorientation. Modern secularity is thus grounded upon the glozed process of conversion that sustains it.[22]

II: Sacrifice and secular conversion in Kreuzweg

‘’You look at yourself in the mirror and think: I look good, my classmates will admire me’’. A tempting scenario, right? Or is it righteous to look away and pray to Saint Mary?’’

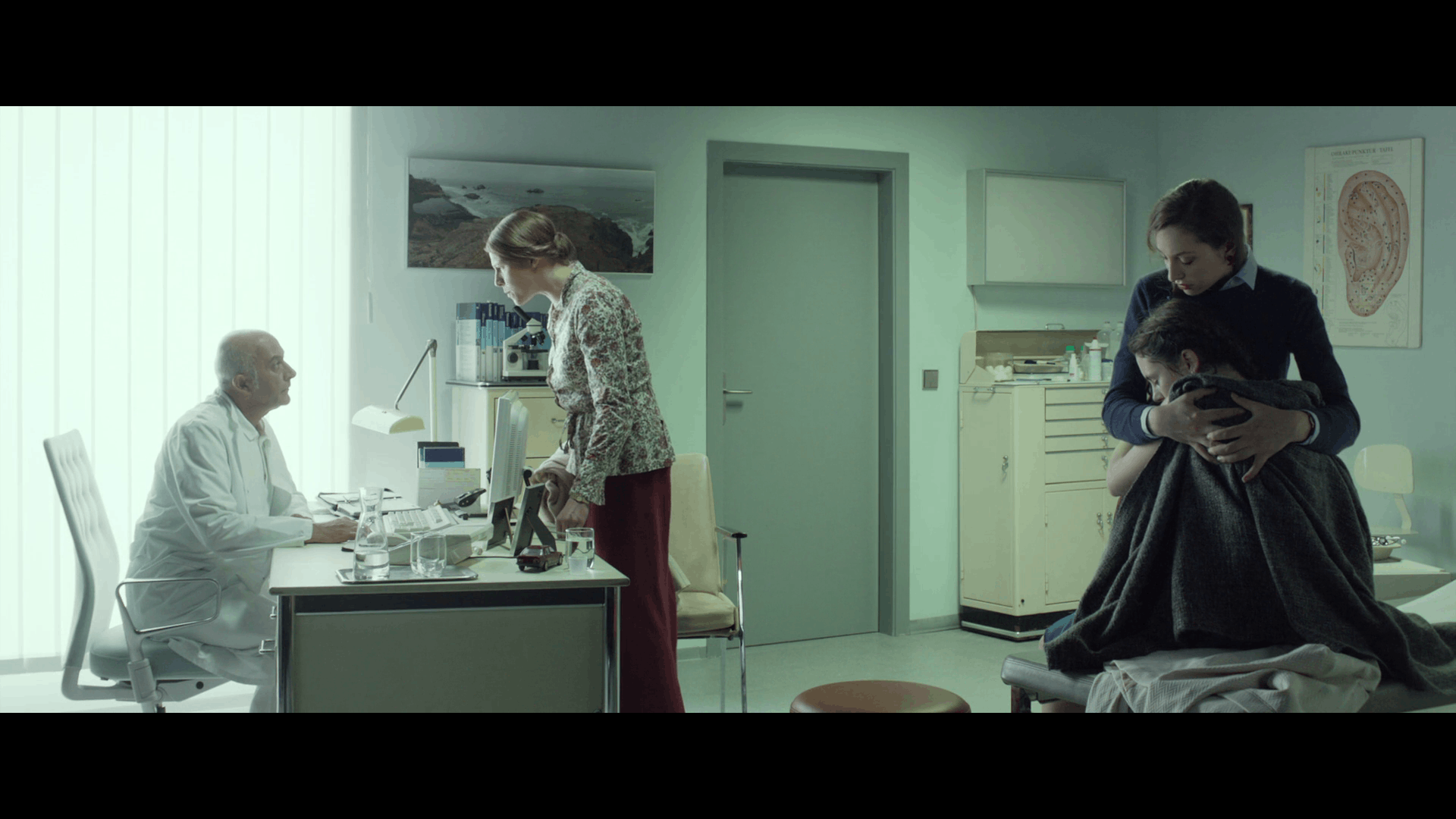

Image 1: the opening scene of Kreuzweg

The opening scene of Dietrich Brüggemans Kreuzweg (or Stations of the Cross, 2014) provides the film with the ideological framework that rigidly haunts the young protagonist throughout the scenes to come. Maria (played by Lea van Acken, the third from the left on image 1) is attending a catechism lecture that is led by a young catholic priest (Florian Stetter). It quickly becomes clear that his instructions are not new to Maria, who is eager to answer most of the questions asked. The priest tells the children that they will become ‘’warriors for Christ’’, underlining that their battlefield lies not in earthly environments, but in their hearts. Although it seems self-evident that the priest doesn’t ask the children to be ‘real’ warriors, he uses the historical example of the so-called Christeros in Mexico, who actually fought an anticlerical government in the 1920s. Furthermore, he firmly criticizes the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), stating that Satan used this occasion to breach the walls of the imaginary fortress Jesus initially used to define the boundaries of his congregation. At this disastrous council, ‘’the devil himself entered the church‘’, luring the Pope and his followers into the rejection of 2000 years of tradition. These historical references are crucial, because they make it impossible to separate the provided religious instructions from a broader ideological and political framework. While the focus of the film irreversibly shifts towards the individual story of Maria, her actions and ideas have to be assessed in line with this very first scene.

I have an additional argument for taking this scene as a defining point of departure. My hypothesis is that Kreuzweg problematizes and criticizes the dominant religious framework of the first scene by showing to which extent Maria’s actions and ideas throughout the film are directly influenced by the priest’s instructions. More particularly, I will argue that the film’s screenplay implicitly proposes a simplistic and specific notion of secular conversion as an alternative. The tragedy of the film lies in the fact that Maria rigidly rejects this notion, thereby (as it were) signing her own death certificate. I will explain how the film aligns Maria’s radical understanding of the concept of sacrifice with the ideological view on sacrifice that is, again, presented in the first scene’s catechisms discussion. The underlying goal is to understand how the film’s proposal of secular conversion is juxtaposed to Maria’s radical religious conversion.

Confirmation and sacrifice

In Kreuzweg, the idea of conversion is made tangible through the formal act of confirmation. According to the priest, confirmation, being one of the seven Catholic sacraments, serves to celebrate the teenagers’ passage to adulthood. Whereas human life starts at the moment of conception, ‘spiritual’ life doesn’t start before the rite of confirmation has been solemnized. The in-group catechism is a preparatory meeting for Maria’s actual confirmation, that ultimately takes place in the ninth (out of a total of fourteen) chapter(s). Thus, you could say that Maria has already been ‘converted’ to Catholicism at the moment the narrative starts. What is actually at stake here is an individual trajectory of change and self-understanding, that is triggered by a specific interpretation of the challenge of ‘sacrifice’.

What then, we may ask first, does sacrifice mean in the Catholic context that we can extract from the film’s screenplay? In the group discussion between the priest and the teenagers, sacrifice is introduced as the most important element of a ‘trinity’ of spiritual sustenance. In order to make room for God in their hearts ‘at all’, according to the priest, the teenagers need sacrifice. When the priest subsequently asks them to sum up some potential sacrifices, they come up with various regular features of their lives: money, food, films, clothes and even ‘time’. ‘’Each time we say no to a cake or a dress, and make a sacrifice instead, we make room for Jesus in our heart’’, is the meeting’s final credo. It is a crucial statement, because it is taken literally by Maria. When the meeting is finished, and the other teenagers have left the room, Maria asks the priest whether or not it is possible to make a sacrifice for someone else, for instance someone who has fallen ill. The priest responds that this is possible, but that illness is often a direct ‘message’ from God. ‘’Sickly children, whose illness gave them time to talk to Jesus, can be like a mirror that shines forth the love of God’’. Maria’s reaction to the priest’s monologue is telling: ‘’[But] what if I wanted to sacrifice my whole life?’’

The question prefigures Maria’s actual self-sacrifice. When you watch the chapters that follow the opening scene with the catechism session in mind, it becomes evident how neatly Maria has attached herself to the priest’s commands. In the second chapter, Maria tries to ‘sacrifice’ her view on the landscape that she beholds during a walk with her family. And at her secondary school, she actually speaks up when the gym teacher uses music with a ‘violent rhythm’ and tempting lyrics.[23] These two occasions of sacrifice respectively ‘spiritual warfare’ are relatively innocent, but what is much more threatening is the lingering threat of deliberate malnutrition, that eventually manifests itself at the confirmation altar (but also before, in van Ackens pale and merely unhealthy appearance).[24] Here, Maria faints at the precise moment she is asked to articulate her vows.[25]

Criticizing ideology

At this point, I want to elaborate on my former statement that the film criticizes the dominant religious framework (i.e. the ideology of the priest) of this scene through its subsequent portrayal of Maria’s actions and ideas. The ninth chapter is the climax of the sacrifice that has been announced in the opening scene. To formulate it more concretely, Maria’s rigid interpretation of the priest’s instructions are the reason that she faints at the altar and eventually dies. In terms of the film’s implicit proposal of ‘conversion’, Maria’s radical understanding of what her own conversion is supposed to entail invites a retrospective focus on the origin(s) of (what turns out to be) self-destruction.

The screenplay makes it evident that both the Catholic authorities (i.e. the priest) and, to a lesser extent, Maria’s parents are the ones with the blood on their hands.[26] All fourteen chapters have titles that correspond to the discursive Catholic ‘Stations of the Cross’, the fourteen stages that are used to describe Jesus Christ’s pathway from death sentence to death tomb.[27] The title of the first chapter in Kreuzweg is ‘Jesus is condemned to death’, which immediately indicates that the film can be read in an allegorical way, especially when you take the film title and the protagonist’s name into account as well.[28] The chapter titles correspond to the ‘Stations of the Cross’ and vice versa, insinuating that Maria is literally condemned to death by the priest at this particular group discussion.

Captivity and the camera

Whereas the script implies that Kreuzweg’s protagonist is the victim of forces beyond her control, the characteristic film style serves to actually exert that control. The first thirteen chapters of Kreuzweg consist of thirteen static frames, in which the actors enact their rigorously separated sequences in single takes. The camera barely moves.[29]

Because the camera is static, Brüggeman has to put great effort in his choices of staging, that means, the extent to which the characters maneuver themselves through film space and how they do it. In the opening chapter, it is quite easy to refrain from editing, since the characters have gathered around the table (see: image 1) and the focus is on dialogue. In the second chapter, though, the movements of the characters through film space has to be sophistically planned, since the camera stubbornly refuses to move along.[30]

Meaning cannot be created through editing anymore, as many directors have done throughout film history. Images cannot be juxtaposed between frames, but this doesn’t exclude juxtapositions within a single frame. Take, for instance, the image that has been inserted below. Brüggeman doesn’t need words to show the alienation between Maria and her mother[31]:

More generally, the static frames in Kreuzweg serve to strengthen the idea that Maria is a girl in captivity. Because the camera doesn’t move, the protagonist is constantly restricted to the limiting space of the separate frames.[32] These frames seem to be metaphors for both the detaining social conditions and the religious framework that have managed to turn Maria into an agent of self-sacrifice. Obviously, one cannot ‘proof’ that the film style of a director and/or a cinematographer (in this case: Alexander Sass) serves to create meaning through the use of the camera. But the argument can definitely be made, especially because these particular stylistic choices are by no means normative for most (contemporary) films[33].

The fourteenth and last chapter contains the strongest example of the film’s style becoming the actual content. The chapter is called ‘Jesus is laid in the tomb’, providing us with yet another reference to the death of Maria as a Christ figure. What we see relates to the title rather directly:

After a few seconds, a boy enters the frame (I will return to this specific feature in the next paragraph) to witness the excavator doing its work.[34] In terms of narrative, nothing special is happening here. The sequence is disenchanting and sober. But then we are surprised by the real climax after the initial anti-climax: the camera starts to move. The uplifting crane shot only ends after a plain view on the clouded spheres of the sky has been established:

This is the final shot of the film. Is anything there? We look at the heavens only to see the sky. It’s an associative ending, because the chapter title has allowed us to think beyond the Stations of the Cross. We see the tomb, but what about resurrection?[35] The question brings me to my final argument on the disempowering potential of the film’s style. If the moving camera is a sign of Maria’s freedom through elevation, that couldn’t be gained in life, the closing shot is the correspondent enervation of that same freedom. There is no afterlife.[36] Thus, the static view of the blue sky reframes Maria’s act of self-sacrifice as an utterly meaningless one.[37]

What we have now is a film that openly criticizes the religious framework that causes the death of the protagonist, doing so by means of a outspokenly detaining film style and a script that is both rigid (the chapter titles) and subtle (some of the prefigurations) at the same time. Although the provided analysis of Brüggemans script for Kreuzweg can do much to explain how a particular movie can frame certain religious convictions (and through it, notions of sacrifice and radical conversion or transformation), the proposed binary between ‘the religious’ and ‘the secular’ has not been made visible yet. In the following paragraph, I will do so by outlining the contours of (what I understand as) the implicitly secular alternative to Maria’s oppressing life conditions. I argue that Maria’s initial embracement and ultimate rejection of this alternative, embodied by a young boy called Christian (Moritz Knapp), serves to express the failure of ‘secular conversion’ within this particular film space.

The implicit manifestation of secular conversion

In the third chapter[38], a modest boy and college fellow-student called Christian establishes initial contact with Maria when they are both studying in the library.[39] Christian helps Maria with some homework and tells her about the church choir that he is in. His references to the church and the choir are ambiguous within Maria’s reflective framework: on the one hand, the choir sings gospel and Bach. On the other, Christian adduces an occasion at which some rock music was played in the church building. This is an indicator of potential evil for Maria, as she responds by saying that this particular genre is often ‘satanically influenced’.

Christian invites Maria to join the choir, and she is evidently eager to do this; in a car trip with her mother (chapter 4), she asks for permission, only to receive a severe tirade as a response. The verdict of Maria’s mother is that Maria can get out and walk home if ‘gospel and jazz’[40] are worth more to her than God and salvation. What is particularly striking here is that Maria doesn’t even tell that a boy invited her (she lies and says it was a girl called Rebecca). When she does so in a later chapter, her mother (predictably) becomes angry again. I argue now, in the first place, that Christian is set apart within the context of the narrative because he represents something, rather than someone, that is forbidden in the context of Maria’s faith. This rigid assessment flows from Christian’s flat character arc; aside from being a love interest, we don’t really get to know him. Nevertheless, Christian is a crucial factor in Maria’s story. In the eighth chapter, Maria rejects his advances and says she doesn’t want to meet up with him anymore. This act generates a clear separation between the religious ideas of Maria and the invitation of Christian to adopt a more flexible mindset. The tragic of Maria’s rejection is emphasized through the next occasion at which we see Christian: he is a powerless eyewitness to Maria’s dead chest entering her grave.

My second argument then is that Christian is the ‘secular’ pole in the religious-secular binary that sustains the narrative of Kreuzweg. A(n) (secular) alternative makes any critique on religious ideology more convincing, because one can look beyond the framework that is rejected through the film’s style and screenplay. The look beyond doesn’t have to be legitimized, because it is, and this is why I interpret Christians position as ‘secular’, this type of conversion to the secular would justify itself, entirely in line with Asads and Scherers reflections on the ways in which most people enter secularity.

My hypothesis (I cannot prove this, since I have no data) is that the role of Christian serves to raise the empathy of spectators, because his offer of love and friendship is something they might relate to.[41] When Maria rejects the offer, only to die in the aftermath, the only thing we can do is mourn with Christian at the grave. We cannot blame him for her death, but we can blame the empty frame of the empty sky, the one that represents Maria’s instructor(s). In the end, the only alternative we have is one that claims to speak for itself.

Conclusion

Matthew Scherer tries to move beyond the religious-secular binary by violating the ‘dictionary’ of the secular. He deliberately uses conversion, a term that is often automatically linked to religious contexts, to gain a more ambivalent understanding of modern secularity. Scherers argument is fundamental for my analysis of Kreuzweg, since I have argued that the film is caught in its paradoxical stance towards conversion as change. On the one hand, the religious conversion of Maria is firmly criticized. Brüggemans script serves to touch upon matters of indoctrination and religious fanaticism. The Catholic Stations of the Cross are mirrored in a rather caustic way, allegorically compiling the different chapters as symptoms of an explicit death sentence. In the meantime, the static framing is a stylistic means to constant emphasis on captivity and oppression. The literal release of the camera in the last chapter connects a temporary sense of freedom to the silence of God. He hasn’t done anything to save Maria.

The attempt of Christian to offer his earthly love to Maria can be seen as an attempt to move beyond the religious-secular binary. Through Maria’s rejection of his love and Christian’s loneliness at her grave, Kreuzweg indirectly affirms the incompatible nature of the religious and the secular. A binary that is generally rejected by academics remains intact in Kreuzweg, a film that fails to acknowledge the irony of its own irony: it criticizes a religious conversion only to propose a secular one.

Bibliography

Books

Asad, T. Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003.

Fitzgerald, T. Discourse on Civility and Barbarity: A Critical History of Religion and Related Categories. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Scherer, M. Beyond Church and State: Democracy, Secularism, and Conversion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Articles

Asad, Talal. ‘’Comments on Conversion’’. Chapter 10 in Conversion to Modernities. London: Routledge University Press, 1996. 263-273.

Balagangadhara, S.N. ‘’On the Dark Side of the ‘’Secular’’: Is the Religious-Secular Distinction a Binary?’’’. Numen 61 (2014): 33-52.

Bolton, Chad W.D. ‘’Stations of the Cross (Kreuzweg)’’. Journal of Religion and Film 19 (2015), issue 2: article 12.

Scherer, M. ‘’Landmarks in the Critical Study of Secularism’’. Cultural Anthropology 26 (2011), issue 4: 621-632.

Scherer, M. ‘’Nietzsche’s Smile: Modern Conversion and the Secularity Craze’’. The Hedgehog Review 17 (2015) nr 3: 56-69.

Wheatley, Catherine. ‘’Present Your Bodies: Film Style and Unknowability in Jessica Hausner’s Lourdes and Dietrich Brüggemann’s Stations of the Cross’’. Religions 7 (2016): 1-22.

Films

Kreuzweg. Directed by Dietrich Brüggemann. 2014. September Film, 2015. DVD.

La Religieuse. Directed by Guillaume Nicloux. 2013. Contact Film, 2013. DVD.

Note: originally I intended to compare and analyze both Kreuzweg and La Religieuse (Guillaume Nicloux, 2013) within the scope of this paper. Unfortunately I had to cancel the paragraphs relating to Nicloux’ film due to space restrictions.

References

[1] S.N. Balagangadhara, ‘’On the Dark Side of the ‘’Secular’’: Is the Religious-Secular Distinction a Binary?’’, Numen 61 (2014), 33, 45.

[2] Balagangadhara states that this triad shows how ‘’the distinction between the secular and religious is not a ‘’modern’’ one, no matter where one locates modernity’’. Balagangadhara, ‘’On the Dark Side of the ‘’Secular’’, 37-38.

[3] M. Scherer, ‘’Landmarks in the Critical Study of Secularism’’, Cultural Anthropology 26 (2011), issue 4, 627.

[4] Balagangadhara, 43.

[5] Balagangadhara, 43-44, 48.

[6] Now the argument of Balagangadhara is that this important status quo has created a problem of simplification and reduction within the secular state’s mode of reasoning, one that actually origins from its wish to be consistent and transparent. Balagangadhara, 46, 49. Individual actors that were either expelled or detracted themselves from narrowly defined religious spheres enter the realm of the secular, doing so, in Balagangadhara’s words, ‘’with false papers’’. Thus the secular state is in a way haunted by a notion of ‘false religion’ within the realm of the secular, precisely because its secular domain consists partly of people that could be ‘’clothed as’’ the ‘’possibly religious’’. Balagangadhara, 44, 49.

Balagangadhara reflects on the actual (presupposed) discursive existence of a phenomenon that I will discuss in the context of cultural products only. Therefore I will not further elaborate on his ideas within the scope of this paper.

[7] T. Fitzgerald, Discourse on Civility and Barbarity: A Critical History of Religion and Related Categories (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 6, 23.

[8] T. Asad, Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003), 25.

[9] This is the main reason why I afford myself to write ‘the’ religious-secular binary within the remaining paragraphs of the paper.

[10] Catherine Wheatley opens her 2016 article on film style in Stations of the Cross (and Lourdes, 2009), by stating that ‘’Since 2005, a number of European films have emerged examining the legacy of Christianity in Western Europe, and the ways in which men, women and children struggle to negotiate questions of religion and secularity, the personal and the institutional, faith and doubt’’. Catherine Wheatley, ‘’Present Your Bodies: Film Style and Unknowability in Jessica Hausner’s Lourdes and Dietrich Brüggemann’s Stations of the Cross’’, Religions 7 (2016), abstract.

[11] In this case, Dietrich Brüggemann directed the film and his sister, Anna, wrote the script.

[12] Wheatley actually involves the views of both Jessica Hausner (for Lourdes) and Dietrich Brüggemann into her argument, and I would be curious to whether or not this really strengthens the prevalent analysis of film style within these two movies. Wheatley, ‘’Present Your Bodies’’, 15.

[13] T. Asad, ‘’Comments on Conversion’’, in Conversion to Modernities (London: Routledge University Press, 1996), 263.

[14] Asad, ‘’Comments on Conversion’’, 263.

[15] Asad, 263.

[16] Asad, 263.

[17] Asad, Formations of the Secular, 186.

[18] In line with the argument of Balagangadhara that I discussed in my introduction, Scherer writes that ‘’the ‘’religious’’ and the ‘’secular’’ are produced through distinct modern grammars that work throughout the process of secularization’’. M. Scherer, Beyond Church and State: Democracy, Secularism and Conversion (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 8. He thus opposes the so-called ‘subtraction story’ that was also criticized by the influential Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor. In the subtraction story, modernity ‘overcame’ religion when people began to think for themselves, thus replacing a more ‘irrational’ worldview with a ‘rational’ one. Premodern naiveté becomes a state of mind that one can fulminate upon, precisely because the secular ‘break’ with religion has a negative connotation of rejection and, in the new context, human evolution.

[19] Scherer, Beyond Church and State, 2.

[20] Scherer notes that he doesn’t want to deny the polysemy of conversion; the term can mean different things in different contexts. What he proposes is only a work definition that serves to understand the transformation towards secularism. Scherer, 8.

[21] M. Scherer, ‘’Nietzsche’s Smile: Modern Conversion and the Secularity Craze’’, The Hedgehog Review 17 (2015) nr 3, 58.

[22] Scherer, ‘’Nietzsche’s Smile’’, 58.

[23] The choice of music is really typical: it’s Roxettes The Look (1988) (‘’She’s a juvenile scam, never was a quitter, tasty like a raindrop, she’s got the look’’). This is the temptation trope played out in the open.

[24] One could note here that the malnutrition directly relates to the instructions of the priest as well. Not only does he list food as a ‘potential sacrifice’ for himself and the children, he also admonishes Maria (be it very lightly and playfully) when she is about to take a sweet at the end of the catechism meeting.

During the confirmation session, two utterances by the priest in charge (not the priest from the catechism) already prefigure the death of Maria. I quote: ‘’Let us pray to the blessed virgin (i.e. Maria, note by the author!), that we may follow her and her divine son, all the way unto death’’ and ‘’She (i.e. Maria again, note by the author) remained true to our Lord all the way to Golgotha’’.

[25] The ninth chapter is called ‘Jesus falls the third time’’, which is a literal (but ironical) reference to Maria’s fainting before the altar. The two chapters that were called respectively ‘’Jesus falls the first time’’ and ‘’Jesus falls the second time’’ only used figurative speech, thus referring to ‘falling’ in a context of (belief in) the normativity of sin.

[26] Unfortunately I am not able to elaborate on the role of the parents within the scope of this paper, because I have decided to focus on the opening scene and the ideology that is evoked there. What I want to state here is that I see the thirteenth chapter as a defining one for the ‘shared guilt’ of the parents, made evident through a talk that Maria’s mother (Franziska Weisz) has with an employee of the involved funeral home. Although the mother has been struck by immensurable grief, she poses two firm religious statements that are, retrospectively, confirming the worldview of the priest and the Church. The first statement is a deliberate refusal of the employee’s claim that ‘different ways lead to Rome’ when it comes to religious convictions. The mother reacts to this quite fiercely, arguing that there is only one true religion. This aligns with the priest’s view on heresy, even within his own episcopal context. The second statement, then, is a somewhat strange and startling note on Maria’s ‘spiritual state of being’ when she died. I quote: ‘’Our daughter lived like a Saint. Evidence indicates that she died free of sin. (…) I consider it highly probable that she died in a state of perfect contrition. And she received the Eucharist on her deathbed’’. That last reference is tragically ironic, since Maria’s bite of a host (given to her by the priest) made her choke and thus caused her eventual death (‘’Holy communion is the best nourishment’’).

[27] The ‘Stations of the Cross’ are usually referred to as a series of paintings, sculptures, or tapestries. ‘’They hang in churches and cathedrals, serving as a reminder of the sacrifice that Christ made for the sake of humankind, intended to inspire contemplation, gratitude and remorse’’. Wheatley, ‘’Present your Bodies’’, 10.

[28] With ‘allegorical’ I refer to the idea that a set of ideas can represent another set of ideas. So in this case, the Gospel story of Jesus’ death mirrors Maria’s pathway to self-sacrifice in Kreuzweg.

[29] It moves three times, to be exact.

[30] The scene features a walk of Maria and her nanny Bernadette towards the camera (see note 28), with Maria’s parents approaching in the background. The narrative deals primarily with dialogue here, and of course Maria and Bernadette stop walking and continue speaking at the moment they have reached the place where the camera has been installed. When the rest of the family arrives and Maria’s mother decides that a picture should be taken, the person with the (mobile) camera leaves the frame, and we only hear the voice. Usually you would expect a shot-reverse shot from the family to the one taking the picture and back; by refusing to work with this regular technique, Brüggemann and his cinematographer affirm their distinct style for this film.

[31] The young woman that embraces Maria is Bernadette (Lucie Aron), the nanny of the family.

[32] Wheatley makes a similar argument: ‘’The film emphasizes its construction, putting the tight framing to double work as it also provides a visual echo of the film’s theme of fundamentalism and oppression’’. Wheatley, ‘’Present Your Bodies’’, 12.

[33] For a good book on normativity and deviance in film style I would recommend, among other works, David Bordwells Figures Traced in Light (2005) and On the History of Film Style (1997).

[34] Note that Maria’s parents leave the film after the thirteenth chapter and do not return in the fourteenth. The boy and the grave digger are the only human beings we see in this closing sequence.

[35] In some versions of the actual ‘Stations of the Cross’, a fifteenth ‘station’ on resurrection has been added. Kreuzweg obviously ends after the fourteenth.

[36] According to Wheatley, too, ‘’the final shot of Stations is resolutely rooted in the natural’’. Wheatley compares the ending of this film with the ending of Lars von Trier’s Breaking the Waves (1996), in which heaven actually does ‘open up’ and we hear church bells cling, implying that the heroine’s sacrifice has been accepted. Also, in Breaking the Waves there is a stylistic break similar to Kreuzweg: ‘’we move from naturalism to supernaturalism in Von Trier’s film, from stasis to movement in Brüggeman’s’’. Wheatley, ‘’Present Your Bodies’’, 17, 19.

[37] Here my argumentation really deviates from Wheatley’s, since her focus is on unknowability. She argues that there are two different interpretations to the closing sequence and (especially to) the moving camera: the first one is fully in line with mine, but the second one aligns the moving camera with the ‘point of view’ of Maria’s spirit rising upwards, to heaven. My response to this second interpretation would be that it is highly unlikely to assume that Kreuzweg moves to supernaturalism here, because the film is so firmly rooted in a firm critique on religion as ideology. Any representation of Maria’s ‘spirit’ after death would weaken the satirical/critical potential of the film that I elaborated upon in my analysis.

[38] ‘Jesus falls the first time’, the chapter title, seems to refer to Maria’s giving in to temptation. The boy shows his personal interest in Maria and she is flattered. Furthermore, the fact that she will ask her mother if she may join the boys’ choir, while lying about his gender identity, proves that the talk in the library has triggered Maria’s ‘desire’ to see him again. Maria eventually confesses this to a priest in chapter five (‘Simon of Cyrene helps Jesus to carry the cross’).

[39] Note the typology that is inherent to the name ‘Christian’ here. My argument would be that Christian, like Maria and the chapter titles, is a part of the allegory that Brüggemann tries to endorse. Since the exact interpretation of this allegory is not the main focus of my paper, I won’t elaborate on this much further (but it is important to see on which levels the names of the characters and the narrative structure influence the film’s potential to convey meaning).

[40] A subtle detail in this regard lies some emphasis on the rigid character of the argumentation: here Maria’s mother says ‘gospel and jazz’, but a few sentences earlier she uses the combination ‘soul and gospel’. This implies that for the mother, these deviant genres are fully interchangeable.

[41] Chad Bolton turns this argument around by stating that (the act of) ‘’watching the ramifications of [that] theological strain play out on screen – progressively worsening until it at last becomes a matter of life and death – leaves little room for emotional neutrality on the part of the viewer’’.

Mooie uiteenzetting, Tim! Ik weet niet of ik de film ooit ga kijken, maar je essay is in ieder geval interessant.

Tx:) het is een film die onvermijdelijk aanzet tot nadenken, al dan niet in positieve zin. Stijl is erg interessant, inhoudelijk is ‘ie doordacht maar niet al te subtiel, zoals je hebt kunnen lezen. Ben wel benieuwd wat je ervan zou vinden.