I wrote the following film analysis for a course called Visual Aesthetics and Analysis (University of Antwerp, october 2017-january 2018). In a (combined) visual and written essay on the movie Final Cut: Ladies and Gentlemen (2012), I argue how the technique of editing & cinematography and the use of music and narrative can contribute to the framing of a darker side of men. My goal is to succesfully connect the analysis of one chosen sequence with a more general thematic evaluation of this special movie.

A darker side of men

Voyeurism and deceit in Final Cut (2012)

Honoring film history

Final Cut: Ladies and Gentlemen is an 84 minutes-long metafilm, in which a compilation of scenes from 450 films form a cleverly edited love story. The film was made by the Hungarian cineast Györgi Pálfi, who noticed the crisis the Hungarian film industry had to deal with back in 2012.[1] Pálfi knew in advance his movie could never become a financial success, because he did not have permission to use all the filmic material included in his final cut. He nevertheless hoped that his movie could somehow get selected for one of the big European film festivals. His dream became true when the prestigious Festival de Cannes premiered his film in 2012.

Making love before the wedding – an introduction to the analyzed scene

In Final Cut: Ladies and Gentlemen, the act of loving and making love is followed by something darker. This observation will steer my analysis of a specific scene from the film, that I will introduce by setting out the foregoing developments.

The intercutted scenes of different men and women making love are preceding the wedding scenes, after which these wedding scenes slowly (i.e. the voice-over tells us that days, months, years go by) fade into the daily lives of the men, sitting behind their desks or dealing with paperwork. A clear distance between the men and the women has been created. This narrative order already helps us to understand that the happiest moments of the couples took place before the weddings.

There is much more at stake though. When the narrative continues after many years have passed (as suggested by the voice-over), the threathening soundtrack on the background functions as a forebode as a man is entering a huge building. While the following cut instantly reveals computers, desks and lots of paperwork (as we would expect), a well-known green codex (appearing on the computer screen of one of these men) proves Pálfi wants to follow another direction. It’s the secret code of the Matrix (1999), implying that something has to be explored or investigated.

Still 1: The Matrix

One piece of dialogue cleares up what is going on here. A colleague of the main character from In the Mood for Love (2000) tells him that he saw his wife yesterday. The next line introduces the origin of deceit, classically framed within the woman’s agency:

Still 2: In the Mood for Love

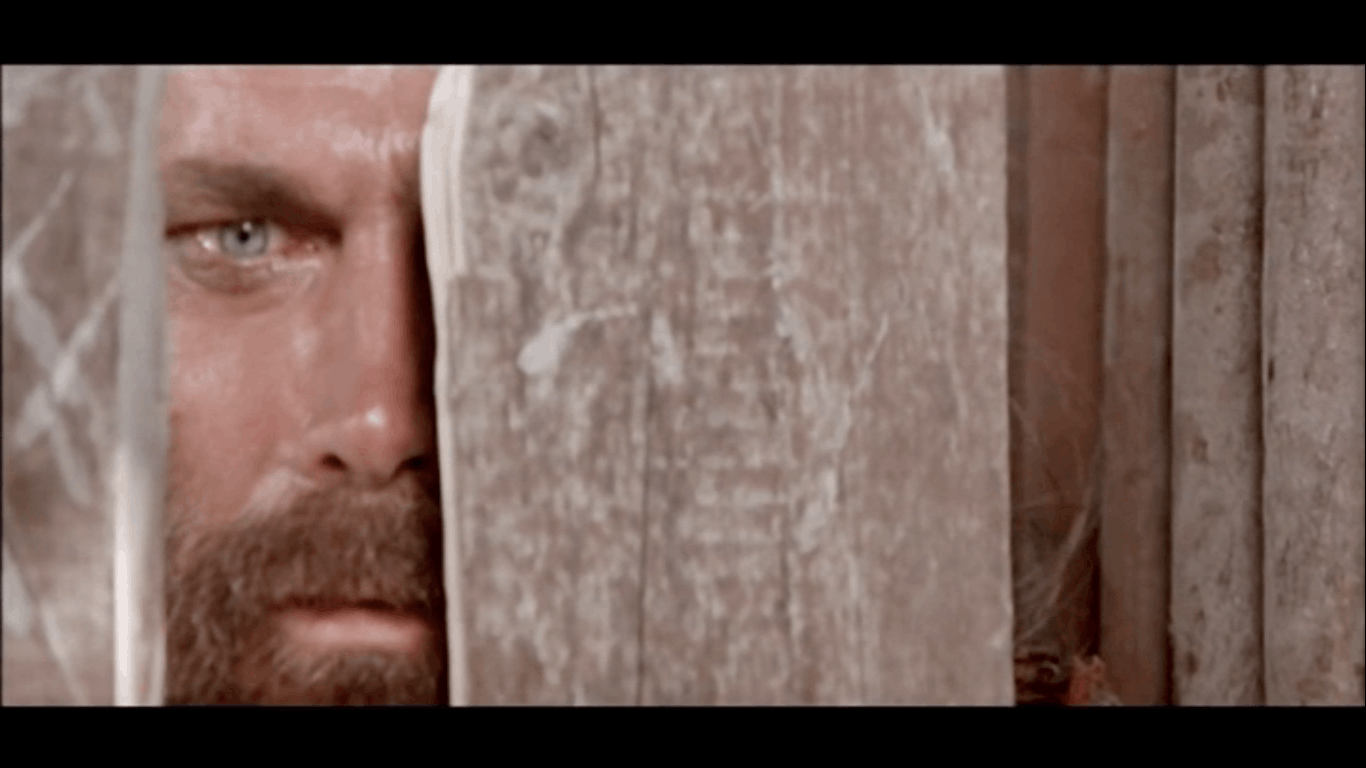

After this revelation, the first two men that are shown look shocked, but the third (Keifer Sutherland, saying ‘that’s none of your business’) and the fourth man already have a cautious gaze upon their face. Pálfi then cuts to Sean Connery cynically (in this context) proclaiming:

Still 3: Sean Connery

Now the women are finally shown, as the soundtrack brightens and we observe them cleaning, cooking and unsuspectingly enjoying daily life. We already know though that deceit has entered the marriage, and it won’t take long before the effects will become visible.

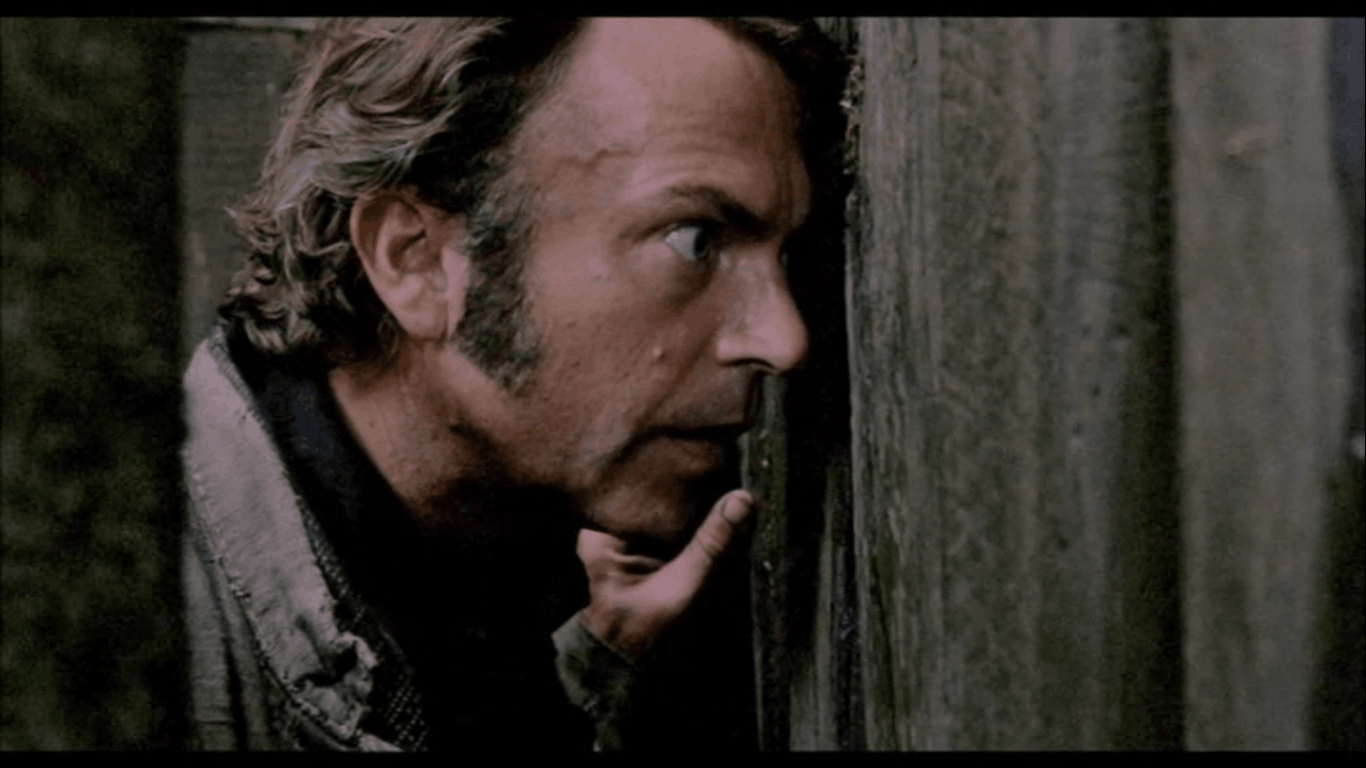

In this analytical essay, I will analyze one specific act that follows upon the revelation of deceit. I firstly pass ten minutes of the movie, in which we see how the men act as self-proclaimed detectives observing and following their wives.[2] Then it becomes darker, and that is where my in depth-analysis starts.

I will focus on two elements: the interplay of narrative and perspective (both on a visual/cinematografic and -again- a narrative plane) and sound/music. Of course editing will be a recurring and vast subject too, as the intercutting of scenes from many movies is the primal creator of meaning in Final Cut. Mise-en-scène and cinematography will only be mentioned when a peculiarity occurs, as my analysis centers around other aspects.

Narrative

Note: I have counted the different shots (seperated by distinguishable cuts), beginning with shot 1 (I used the term still for the images used in the introduction) at 47.55 and ending with shot 42 at 50.26. It will thus be clear when a shot is left out because it was too repetitive or because it didn’t explicitly add something to the analysis.

Different women have arrived at another location than their own home, i.e. the location where their supposed secret lover awaits them. The women ring the doorbell, the men open the door and let the women in. This is where my analysis starts:

Shot 2: the well-clothed gentleman

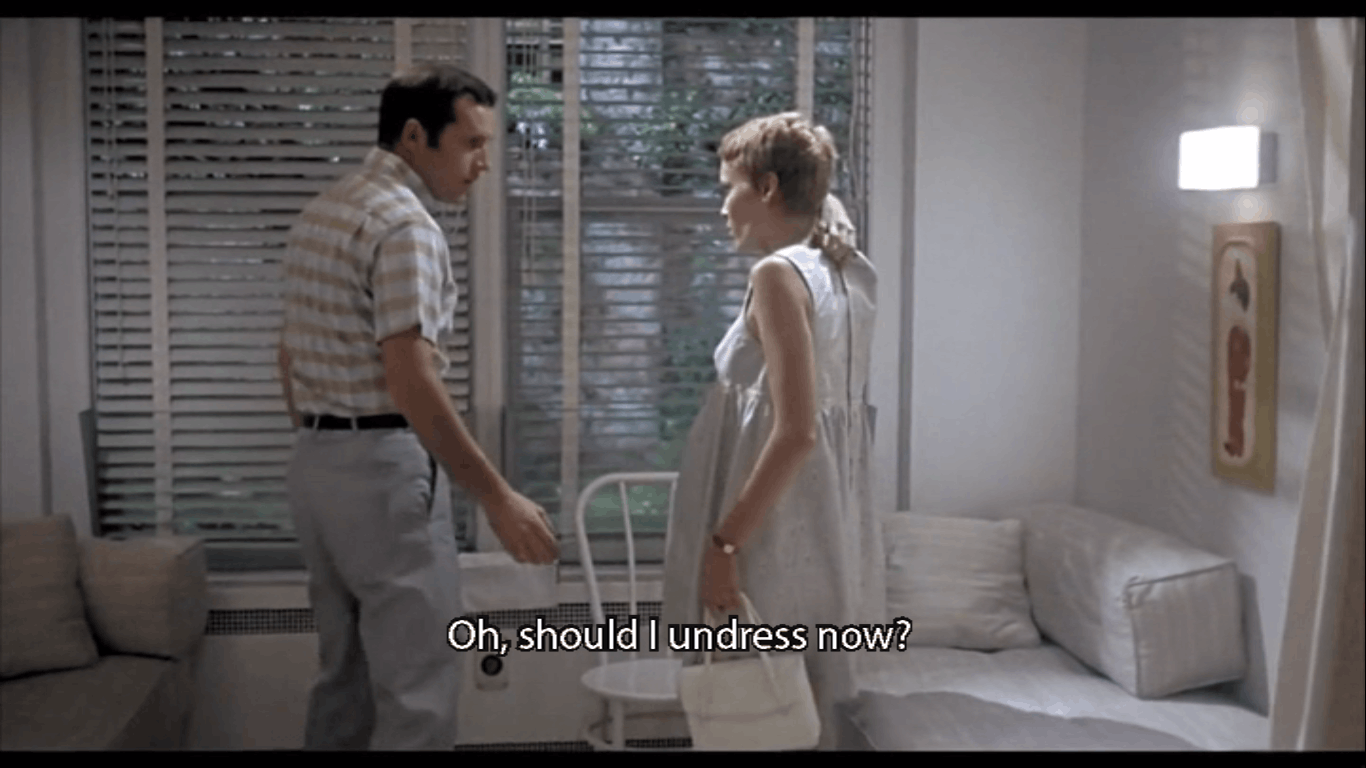

The shot shared by the well-clothed gentleman and the arriving woman is followed by a short scene showing Mia Farrow in Rosemary’s Baby (1968). This is an interesting one, because one specific line of dialogue implies Mia Farrow is with this man for other purposes:

Shot 3: Mia Farrow

Farrow subsequently asks: ‘should I undress now?’ You wouldn’t expect this question coming from a woman who is cheating on her husband. She wouldn’t be so passive, and if she would, the man would behave different and/or ask other questions. Furthermore there is a relevant distance between the characters, emphasizing that sexual tension is lacking or, in this case, just not present. Instead the man seems to be a doctor, implied by the verb ‘checking out’ and the conventional question (in such a context) asked by Farrow.

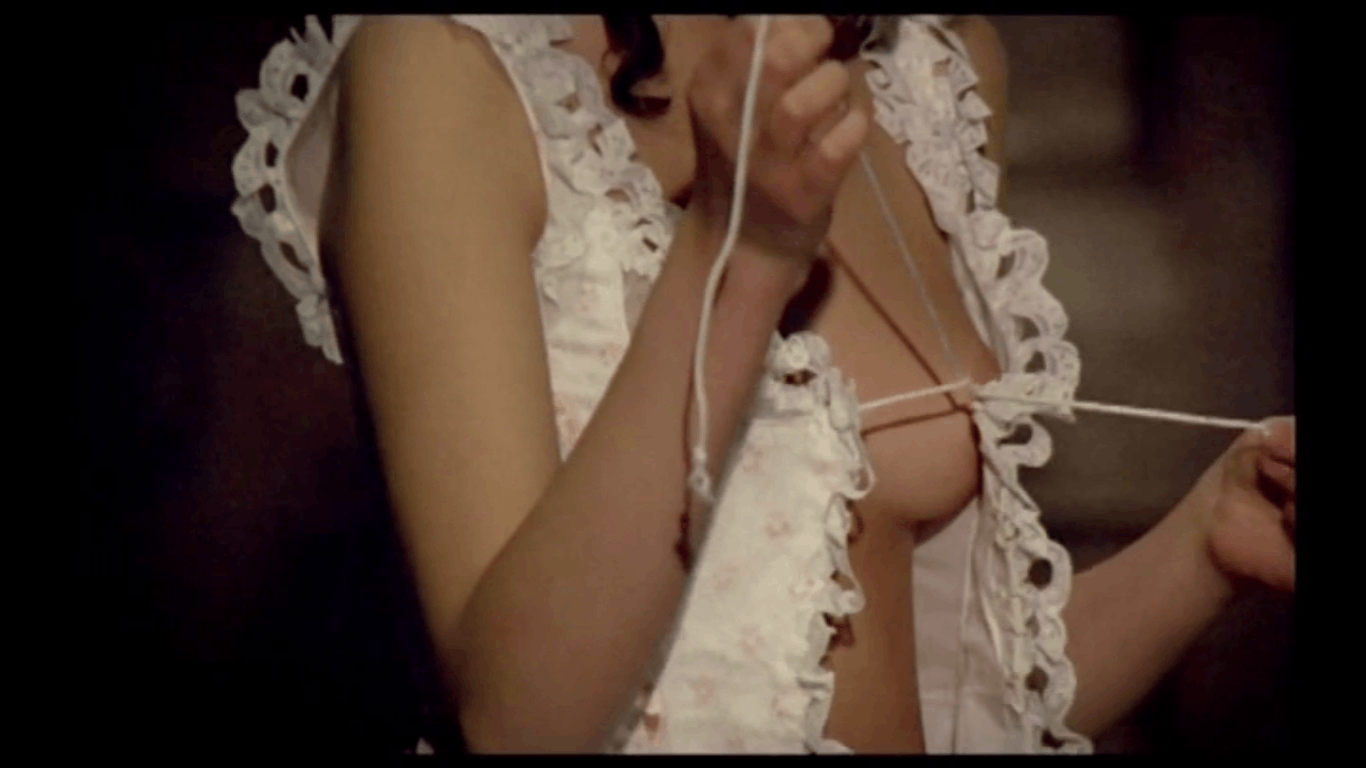

This confusing revelation is nevertheless followed by fast cuts of a few women undressing (shot 7 and 14), while the gazes of different men (shot 6 and 10) clearly communicate the act of voyeurism:

Normally we would be inclined to believe that these gazes respond to the act of cheating (as initiated by the women), but the short scene with Farrow has made things complicated. Not only are the men secretly looking at these female bodies (shown in close-up, thus being the explicit object of the male gaze), the men we would expect to be present are not visible. Are they even here at all? Or are we only witnessing the act of looking in the dark? Purely on a visual plane, this is the case.

In all these shots, the mise-en-scène (I especially mean the production design here) is quite sober, forcing us to focus on both the act of viewing (through windows or holes in the wall) and the bodies of the viewed. The lighting is quite dark in most of the shots concerning the men. The shots portraying the bodies are usually lighter, hypothetically because there is a body to accentuate (shot 11 or 14). This supports the idea of male voyeurism or gazing, as constructed through the perspectives of both the filmic and the actual viewers.

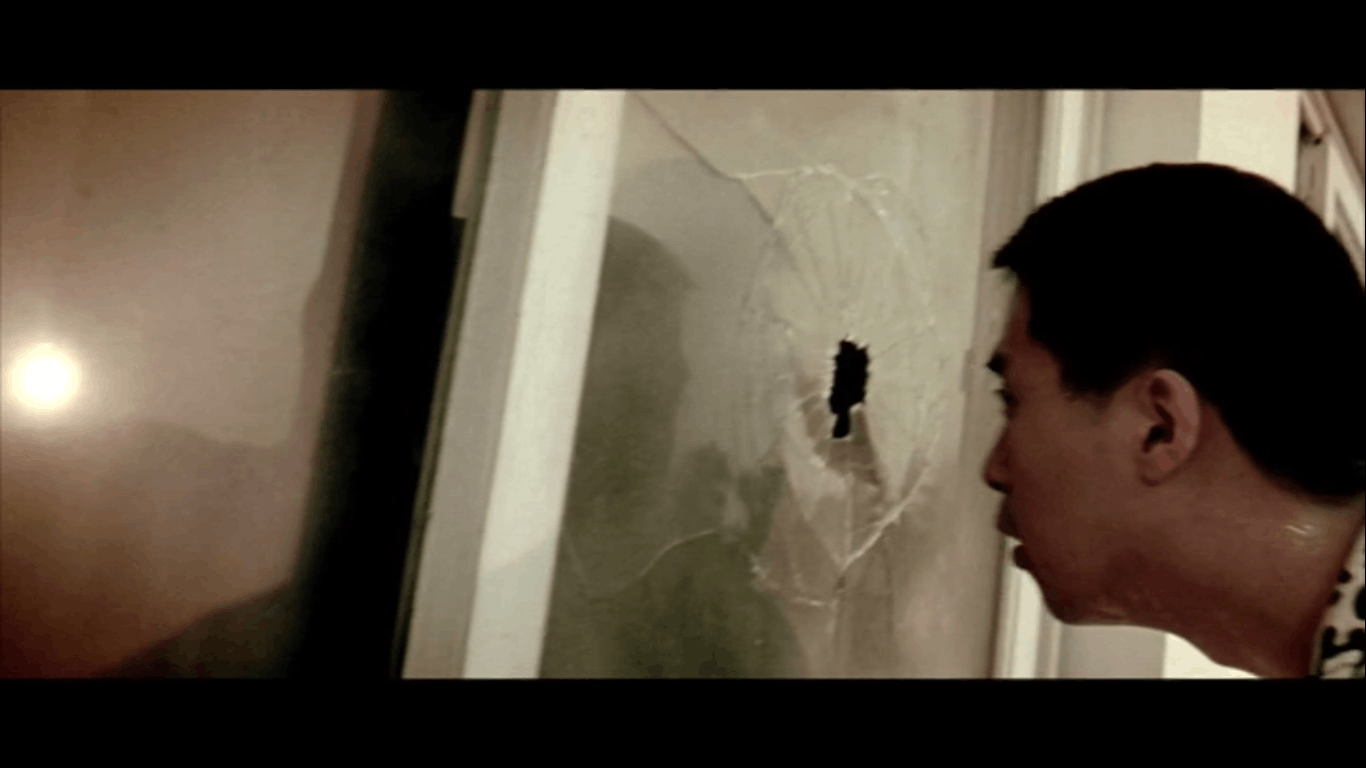

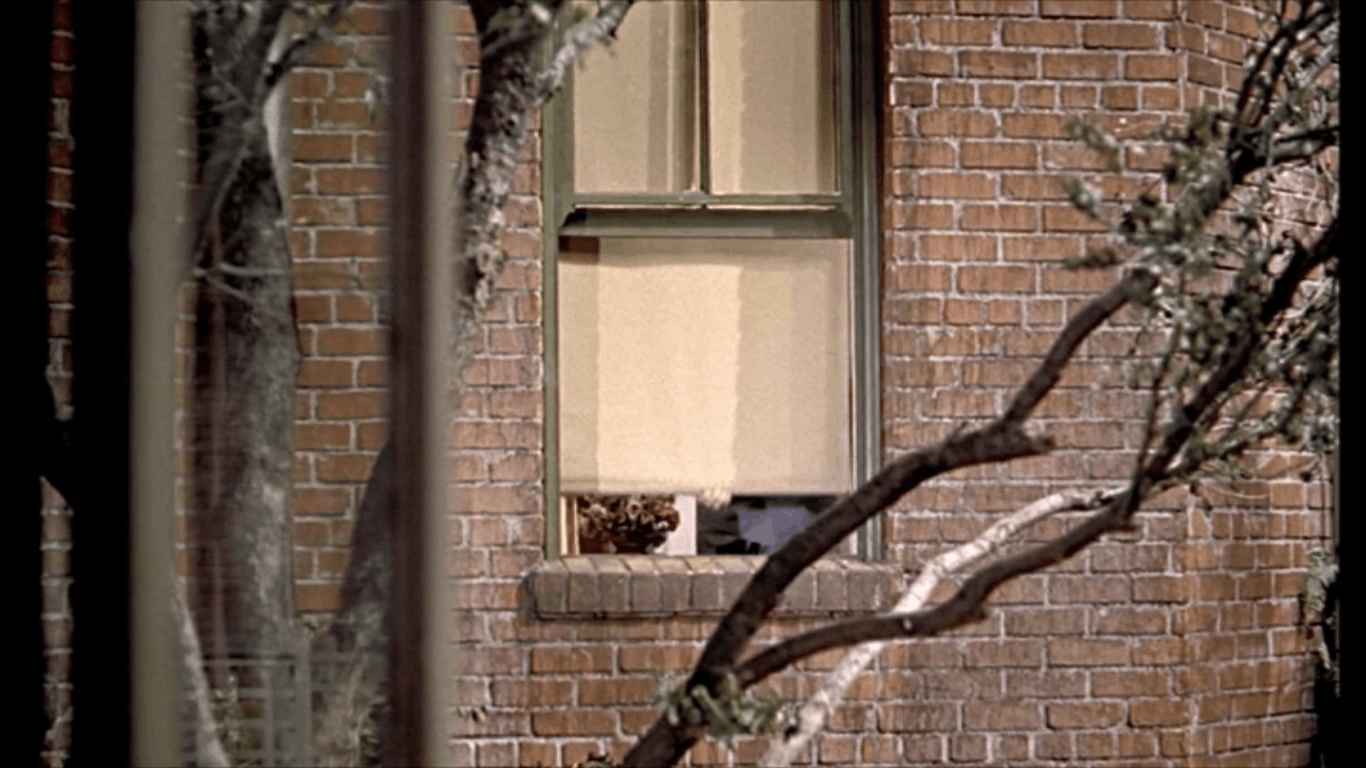

The women appear alone (shot 11), the men act like they are witnessing something they’re not meant to see. They are consciously moving towards the window that allow them to watch (shot 4) or the camera functions as the eye of the viewer, tilting from the breasts of a woman towards her legs (best seen with the tilt movement included).

Shot 11

Shot 4: the male viewer

Although we now appear to observe the act of voyeurism on itself, the narrative soon reconnects with the act of jealousy and deceit. The primar indicator for this is the music and sound that is used in this part of the film.

Where does this shift from voyeurism back towards the involvement of other men appear? Well, first the act of voyeurism must be stopped or countered. The female bodies have to disappear in order to create the disillusion or even disappointman of the one who watches. Note how this shot (21):

Follows upon this one (20):

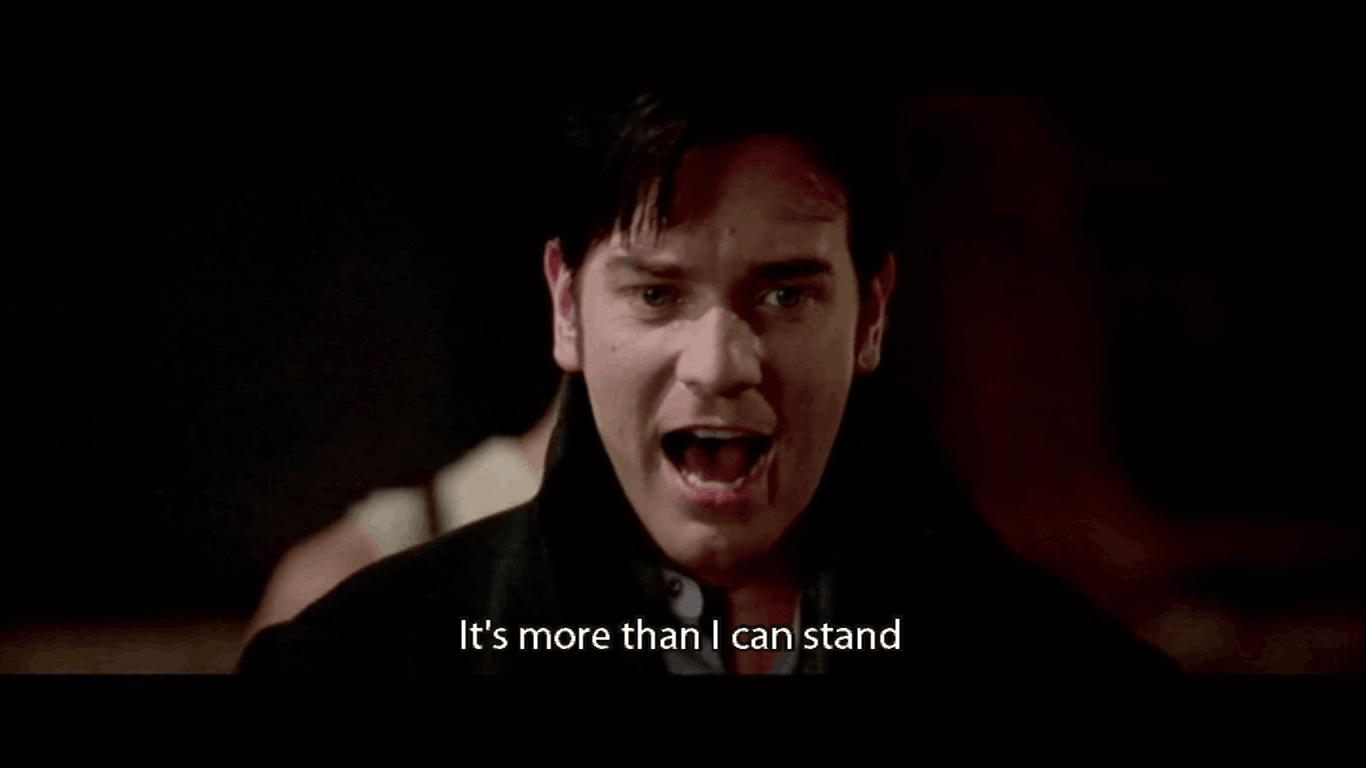

The women have noted that someone has been watching her, and subsequently close the curtain (this happens three times within one or two seconds) for both the diegetic voyeur and the non-diegetic spectator. This act ultimately causes the disillusion of the different men, edited together by a soundtrack from Baz Luhrmanns Moulin Rouge (2001). The lyrics (from the used part of El Tango de Roxanne, mainly sung by Ewan McGregors Christian) are as follows:

His eyes upon your face

His hand upon your hand

His lips caress your skin

It’s more than I can stand!

Why does my heart cry?

Feelings I can’t fight!

You’re free to leave me but

Just don’t deceive me!

…and please believe me when I say

I love you!

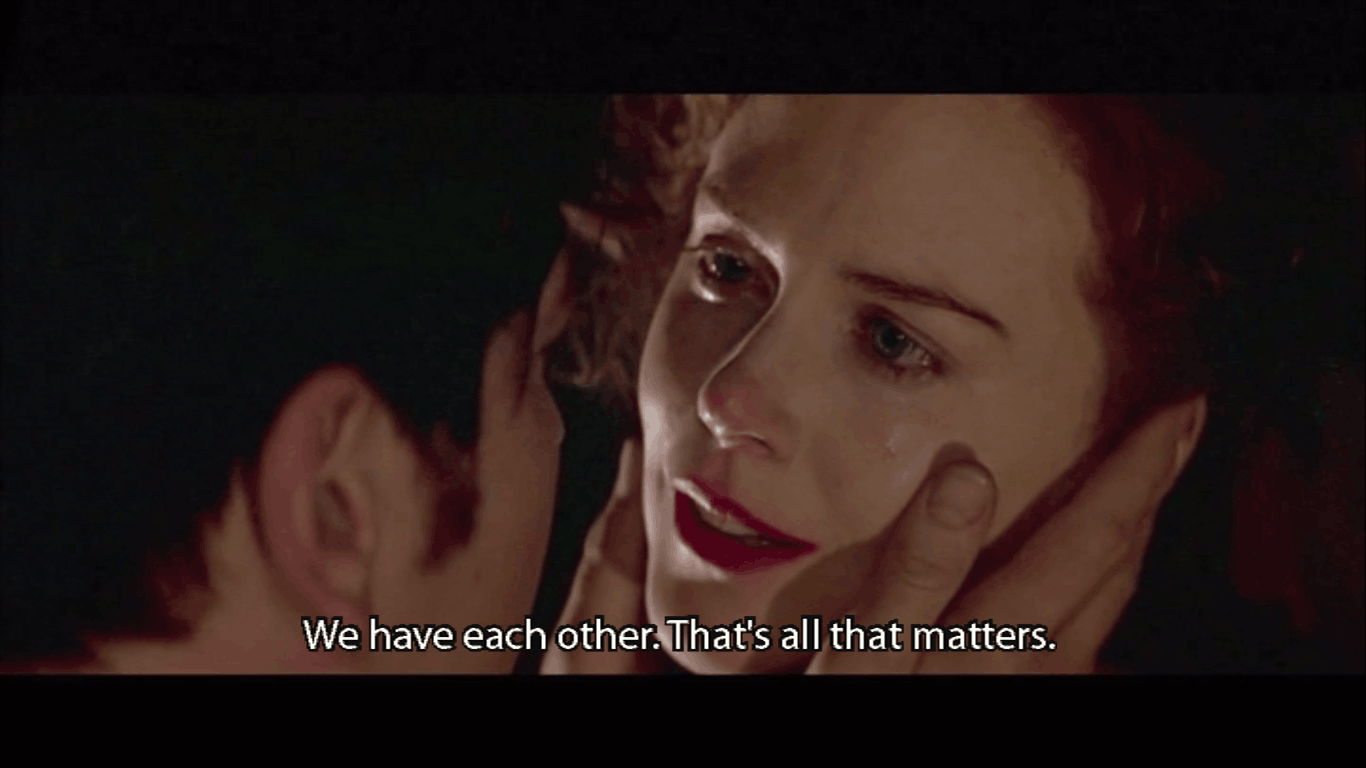

What’s especially relevant here is that El Tango de Roxanne in first instance seems to be a non-diegetic track, but later becomes diegetic when Ewan McGregor himself appears in shot 28:

Although the meaning of the song is projected upon many characters, we actually get to see the specific diegesis of the music. El Tango de Roxanne is sung in Moulin Rouge when the experience of a loved one (played by Nicole Kidman) being with a manipulating count (played by Richard Roxburgh) is tearing the main character apart. Christian cannot bear the thought of deceit, the thought of his muze being with another man. That is the context for this part of the film, emphasized by the short (=only one second) use of sex sounds in this specific shot (26) from Kubricks A Clockwork Orange (1971):

The theme of deceit, jealousy and frustration is back on track, and that is what makes the foregoing shots even more interesting. The clear motive of the portayed men (‘his lips caress your skin’) is questioned by the act of voyeurism that preceded. There is a darker side, a fetisjistic gaze that stays unexplained while the narrative continues. What seems to be a conventional love story, told by constantly intercutted shots, appears to be meandering in ambiguity.

Epilogue

I had almost forgotten the dark times that lied ahead when I was watching the last five minutes of this movie for the first time. For a long time, I thought that there would be a happy ending. We even see how Christian and his loved one are reunited again:

Still 4: Moulin Rouge, Ewan McGregor with Nicole Kidman

Three shots later, Nicholas Cage starts singing the well-known Love me Tender-ballad (in David Lynch’s 1990 roadmovie Wild at Heart), and everything seems to be just fine. But then the music fades and a more threathening sound enters the last diegetic world we see in Final Cut. These are three screenshots (taken in succession) from the last scene:

The last, somewhat unsharp image of a vampire’s teeth moving towards the neck of his victim is the last one we see before The Final Cut literally does its final cut. We don’t see the actual deed that follows the movement downwards, but we can fill in the gap: the girl will die, and thus the woman is reduced to nothing more than a prey, an object that can either love or die. Dealing with The Final Cut as a meta-story, built upon scenes from the entire history of film, this final cut is both the boldest and the most horrific statement Pálfi could make.

[1] Palfi Gyorgy “Final Cut – Ladies and Gentlemen” Interview – Cannes Film Festival 2012. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J1hCCRWhOvg. Seen on the 7th of January, 2018.

[2] I strongly recommend the reader to (at least) watch the twenty minutes preceding the analyzed scene before he or she reads the analysis.

Interessante in-dept blik in Final Cut! Heb ik sowieso een enorm bijzondere film gevonden.

Is het ook. Gaaf dat je em al gezien hebt. Toch een wat minder bekende niche-titel