This essay was written in the context of a RMA course on Materiality and the Body in the study of religion, spring 2019.

Queen B and her Beyhive

Iconic Power in the human realm

In their introduction to Materiality and Meaning in Social Life (2012), Dominik Bartmánski and Jeffrey C. Alexander respond to a tendency in the social sciences and cultural studies that equals materiality and disenchantment, objects and capitalist commodification.[1] In the particular case of iconicity and iconic power, a lack of attention for aesthetics and the social construction of meaning has ‘’either disregarded or stigmatized the metaphorical and emotional power of economic objects.’’[2] Bartmánski and Alexander propose a conception of icons in which they are conceived of as transmitters of experience, that encourage us to interact with them.[3] They write that ‘’ Icons allow members of societies (1) to experience a sense of participation in something fundamental whose fuller meaning eludes their comprehension and (2) to enjoy the possibility for control despite being unable to access directly the script that lies beneath.’’ Moreover, ‘’Icons are cultural constructions that provide believer-friendly epiphanies and customer- friendly images’’.[4]

While I can perfectly follow Bartmánski and Alexander’s argument, there is one thing I do miss in their understanding of icons: it appears to be confined to material objects, solely granting ‘iconic consciousness’ to the actors able to feel the sensual and aesthetic force of an icon.[5] Therefore I pose my thesis for this entry as a question: to which extent is it possible to extend Bartmanski and Alexander’s material understanding of ‘iconicity’ and ‘iconic power’ to the realm of human actors, or better, human icons? My hypothesis is that one of the authors’ core quotes on icons and iconic power by no means excludes the idea that human beings could also serve as icons and/or perform iconicity. I quote: ‘’icons allow members of societies (1) to experience a sense of participation in something fundamental whose fuller meaning eludes their comprehension and (2) to enjoy the possibility for control despite being unable to access directly the script that lies beneath.’’ Moreover, ‘’icons are cultural constructions that provide believer-friendly epiphanies and customer- friendly images’’.[6]

I tried to find some instances on the internet where human beings were entitled ‘icons’ (Dutch: iconen). I found many:

- An exposition on Toetanchamon frames the farao as a ‘pop icon’: https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2019/03/22/expo-over-toetanchamon-belicht-farao-als-pop-icoon-a3954261.

- Che Guevera is said to be a pop icon in an article on Guevera imagery: https://nos.nl/artikel/2197112-de-foto-die-van-che-guevara-een-pop-icoon-maakte.html

- Many pop artists are quoted ‘’pop icons’’; Prince, David Bowie, Madonna, and so on.

I could mention more examples, but my case here is to take one recent example (a news article, see: https://nos.nl/artikel/2280935-in-de-vs-hebben-ze-geen-koningin-dus-is-beyonce-dat-geworden.html) and to conduct a concise analysis that compares and aligns a) the text of the example b) fragments from Beyoncé’s own website and the core passage on icons. This case study was inspired by a NOS (Dutch broadcast system) news item on Beyoncé’s new album ‘Homecoming’, which was released on-and offline at Wednesday 17th, 2019, together with a Netflix documentary showing the popstar’s preparation on her performance at the Coachella music festival (14 & 21 April, 2018).[7] Beyoncé Knowles (1981) is an American singer and actress who is most famous for her partaking in R&B group Destiny’s Child (1997-2005) and her later solo career, featuring hit singles like Single Ladies (Put a Ring on it) (2008) and Run the World (Girls) (2011).

Participation in something fundamental

The key to Beyoncé’s success is that her brand is not solely based on her performances; according to ‘persona experts’ [imagodeskundigen], we read in the article, the singer has become an icon of feminism, activism and philanthropy. Beyoncé’s basic identity as a singer and performer extends itself to a ‘fundamental’ level because the topics she addresses and embodies are relevant, both to society and to her fans.

In the article, the idea of ‘persona’ and the construction of it is closely connected to Beyoncé’s status as a pop icon:

‘’Een belangrijk aspect van het opbouwen van een imago is het inspelen op wat populair is, legt Van Veen [een ‘imagodeskundige’, red.] uit. “Je kijkt naar de topics van het moment. Je merkt nu bijvoorbeeld dat steeds meer jonge vrouwen er goed uit willen zien, maar ook goed willen zijn in hun werk. Ze willen een plek als vrouw in de maatschappij, niet als een vrouw die zich moet aanpassen. Daar speelt Beyoncé op in. Dat topic pakt ze op, maar ze staat ook achter dat feminisme.”

Beyoncé at Coachella 2018. Source: Elite Daily.

Van Veen mentions young women, and indeed, her appearance as a pop star attracts women who take Beyoncé as an example of ‘how-to-be’. Beyoncé’s overall popularity, however, does not limit itself to any ill-defined sociodemographic group. “Ze is een moeder, zakenvrouw, filantroop, feminist, activist en een hele goede artiest. Je kunt haar goed vinden of je nou een wit of zwart bent, man of vrouw”[8], Van Veen states in the article. Both women and men, young and old, can partake in the sociopolitical issues [Black Lives Matter/civil rights, women’s rights & gender equality] that she addresses, while her performances in and on themselves might be out of their reach[9].

The possibility of control despite a lack of access to the script

All Beyoncé’s fans can decide to mimic the issues and topic that she addresses, but that does not take away the fact that there is a hierarchy or a distance that is upheld by the singer herself. The following comment is from Lize, a Beyoncé fan who talked to radio station 3FM:

“In haar video’s zet ze zichzelf neer als een koningin waar iedereen voor moet buigen. Het past natuurlijk wel bij haar imago, maar gaat soms wel wat ver.”[10]

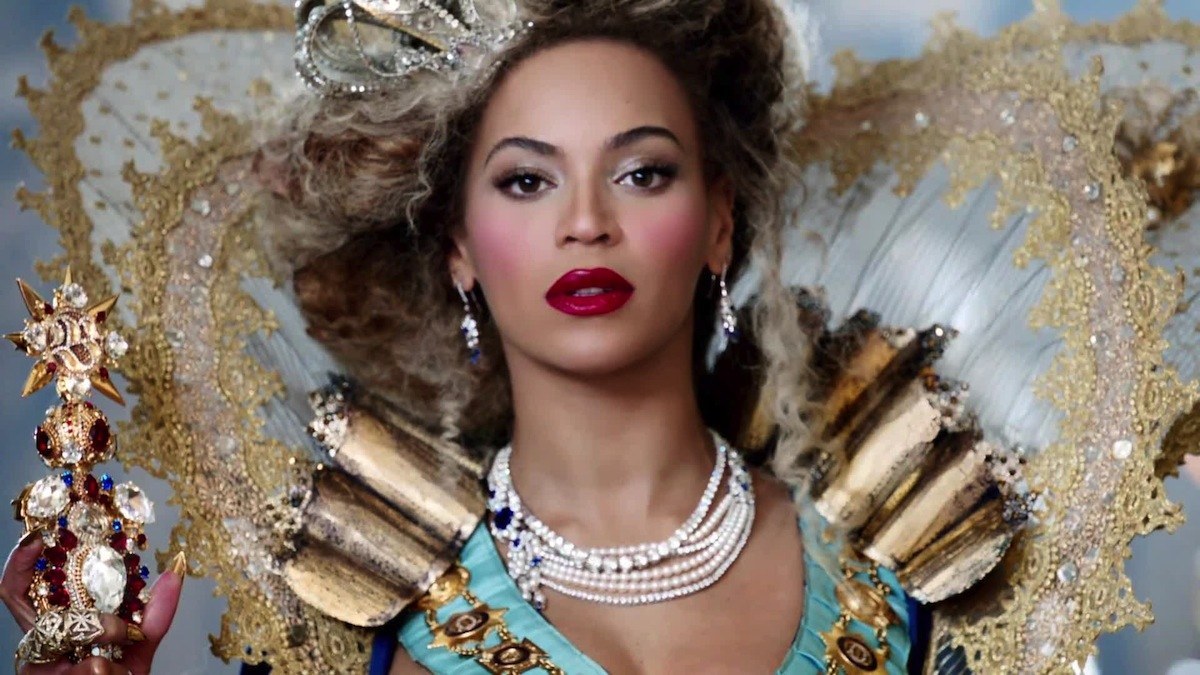

Quuen B, source: Zimbio.

Beyoncé’s fans, in other words, have no access to the script of Queen B, which has been Beyoncé’s nick name or brand name for years. On the other hand, there is actually a possibility of control. Within this fascinating paradox, Beyoncé-fans can sign up on her official website to join the ‘Beyhive’, a fanbase that guarantees ‘’advance access to news, special experiences, exclusive merchandise, and more’’.[11]

The Beyhive, image from Beyonce.com.

Believer-friendly epiphanies

Beyoncé’s framing as a ‘Queen’ for whom everyone has to bow makes it intelligible to speak of ‘believers’ who can get access to epiphanies or ‘special experiences’ (see the website) once they become a fan. It even becomes difficult to resist; the NOS article closes with a statement from van Veen on critique and jealousy: ‘’als iemand heel populair is, en jij zegt daar negatieve dingen over: dan doet dat afbreuk aan jouw imago. Dus wees slim, mensen gaan die kritiek vooral zien als jaloezie.”

To conclude, Beyoncé’s iconic power neatly fits the description of Bartmánski and Alexander that ‘’icons allow members of societies (1) to experience a sense of participation in something fundamental whose fuller meaning eludes their comprehension and (2) to enjoy the possibility for control despite being unable to access directly the script that lies beneath.’’[12] The case study also demonstrates how ‘’[human, red.]icons are cultural constructions that provide believer-friendly epiphanies and customer- friendly images’’.[13] I hope this comprehension of iconic power can help to further consider extension of this conceptualization into the human realm.

Bibliography

Bartmánski, D. and J.C. Alexander. ‘’Introduction: Materiality and Meaning in Social Life: Toward an Iconic Turn in Cultural Sociology’’. In J.C. Alexander, D. Bartmánski and B. Giesen, eds., Iconic Power: Materiality and Meaning in Social Life. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2012.

Notes

[1] D. Bartmánski and J.C. Alexander, ‘’Introduction: Materiality and Meaning in Social Life: Toward an Iconic Turn in Cultural Sociology’’, in J.C. Alexander, D. Bartmánski and B. Giesen, eds., Iconic Power: Materiality and Meaning in Social Life (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2012), 1.

[2] Bartmánski and Alexander, ‘’Introduction’’, 1.

[3] Bartmánski and Alexander, ‘’Introduction’’, 3-4.

[4] Bartmánski and Alexander, ‘’Introduction’’, 2.

[5] Bartmánski and Alexander, ‘’Introduction’’, 1.

[6] Bartmánski and Alexander, ‘’Introduction’’, 2.

[7] https://nos.nl/artikel/2227412-beyonce-schrijft-geschiedenis-met-optreden-coachella.html . Accessed March 20th, 2019.

[8] See also: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-04-27/beyonces-homecoming-shows-why-we-should-all-be-fans/11046928. Accessed March 29th, 2019.

[9] [with a blink]: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Sqm9mf5x0Q. Accessed March 28th, 2019.

[10] See: https://www.npo3fm.nl/nieuws/3fm/375821-hoe-beyonce-aan-haar-hoge-status-komt. Accessed March 29th, 2019.

[11] https://www.beyonce.com/register/. Accessed March 29th, 2019.

[12] Bartmánski and Alexander, ‘’Introduction’’, 2.

[13] Bartmánski and Alexander, ‘’Introduction’’, 2.

Een gedachte over “Beyoncé: Iconic Power in the Human Realm [Essay]”